Accessibility and Affordability

Delivering Affordable, Accessible Products

Category C consists of two criteria:

- C1 Product Pricing

- C2 Product Distribution

To perform well in this category, companies should:

- Make clear, formalized commitments that extend to a clear strategy, with Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound (SMART) targets to promote the affordability of their healthier products (according to the company’s definition) over less healthy products, and with low-income consumers in mind.

- Provide evidence of conducting pricing analyses to appropriately price healthy products and of improving the price differential between ‘healthy’ vs. less ‘healthy’ products.

- Disclose commitments, targets and a strategy to improve affordability of ‘healthy’ products.

- Make clear, formalized commitments that extend to a clear strategy, with Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound (SMART) targets to promote the accessibility of their healthier products (according to the company’s definition) over less healthy products, and with food-insecure groups in mind.

- Take steps to improve the accessibility of ‘healthy’ products for low-income/food-insecure households, such as seeking arrangements with retailers and distributors to ensure the distribution and availability of healthy products nationwide.

- Have a policy in place to ensure responsible food donations, with clear prioritization of healthy products, and show evidence that the vast majority of their food donations are healthy.

- Disclose commitments, targets, and a strategy to improve access to ‘healthy’ products.

Ranking

- C1

- Product pricing

- C2

- Product distribution

Overall, there was slight improvement in Category C, but overall scores remain low, averaging at 1.5, and the highest score remains under 4. Kellogg continues to score the highest in this category, with commitments and actions in place for both affordability and, especially, the accessibility of products it defines as healthy. Unilever demonstrates the greatest improvement, having developed new affordability strategies for one its healthier brands in the US, scoring 3.2 (a sizeable increase from 0.1 in 2018).

Category Context

According to the American Heart Association (AHA), ‘affordability’ means that nutritious foods are available at a cost that is accessible to all individuals, including those on low incomes. The current climate of rising inflation, which reached the highest rate in 40 years in the US in April 2022, accentuates the urgency of addressing the affordability of healthy foods relative to unhealthy foods. With low-income households spending an average of 30% of their income on food (compared to 10% for the average American household), as costs of living soar, price considerations inevitably supersede nutrition quality as a priority for millions of Americans. Given that less healthy foods are typically cheaper than healthy options, the cost-of-living crisis could further exacerbate the obesity epidemic: numerous studies have found a strong correlation between food insecurity and obesity in the US. Therefore, food & beverage manufacturers can make a real difference by offering a wide range of nutritious products at affordable prices at a greater rate than less healthy products.

For this report, ‘accessibility’ means that nutritious foods are readily obtainable by individuals in all geographic locations. According to the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans, access is “influenced by diverse factors, such as proximity to food retail outlets (e.g., the number and types of stores in an area), ability to prepare one’s own meals or eat independently, and the availability of personal or public transportation. The underlying socioeconomic characteristics of a neighborhood also may influence an individual’s ability to access foods to support healthy eating patterns.”

The US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 2017 study on food access found that 39m people (12%) in the US live in low-access communities – where at least a third of the population lives over a mile from a supermarket or large grocery store (in urban areas), or more than ten miles away (in rural areas). These are associated with low access to affordable fruits, vegetables, wholegrains, low‐fat milk, and other foods that make up a healthy diet. One study has also found a positive association between living in low-access communities and obesity.

While the US has extensive federal assistance programs that provide a safety net to addressing basic food security (see Box 1), food manufacturers, apart from providing the food and beverage products for these programs, still have a significant responsibility to advance nutrition security through their own commercial operations. As SNAP has no restrictions on monthly benefits being spent on unhealthy products, if these remain cheaper and/or more accessible, low-income consumers may continue to prioritize them to meet their basic needs. By providing their healthy products at lower prices and ensuring adequate distribution in low-income areas, companies can encourage participants, as well as the general consumer, to choose healthier foods. Moreover, given that many households that are food-insecure are either ineligible for either SNAP or WIC or do not participate (for a variety of reasons), addressing the affordability of healthy products in general is still highly relevant.

The US Government in the September 2022 National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition and Health announced actions to further increase access to free and nourishing school meals; providing Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) benefits to more children; and to expand the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) eligibility to more underserved populations.

The charitable food system and food banking are other major means by which food access and affordability are addressed in the US for low-income consumers: 6.7% of all US households reported using a food pantry in 2020, up from 4.4% pre-pandemic. Over the last decade, the food & beverage industry has contributed vast sums – both in cash and in-kind – to food banking organizations and networks as part of their philanthropy efforts, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, donations of unhealthy products have been cause for alarm for stakeholders over the last decade (including during the pandemic), as these can exacerbate poor nutrition issues. For example, a 2018 report found that one-quarter of food distributed through food banks consisted of unhealthy beverages and snack foods – and while more than half of food banks track the nutritional quality of donations and/or have nutritional guidelines, nearly 40% face difficulties in knowing how to handle unwanted food & beverage donations.

Therefore, it is essential that companies, as a minimum, have policies to limit the amount of less healthy foods donated and that they, ideally, provide predominantly healthy products to improve the diets and health of people dependent on food banks. To this end, in 2020 Healthy Eating Research (HER) developed nutrition guidelines for charitable food systems, which were adopted by Feeding America. Most importantly, however: companies need to make efforts to remove some of the systemic barriers to the consumption of healthy products by addressing affordability and accessibility in their commercial operations.

Box 1. US Federal Assistance Programs: SNAP and WIC

The US has several federal assistance programs to combat food insecurity among low-income consumers, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). SNAP benefits are currently claimed by 41.5m people, increasing by 17% between February 2020 and April 2021. Recipients receive a monthly benefit that can be used to buy food and non-alcoholic beverages in many retailers and convenience stores (restaurants are excluded). In August 2021, this monthly benefit per person was increased by 25%, to an average of USD 161, to reflect the cost of a healthy diet as defined by the revised ‘Thrifty Food Plan.’ Much of this money is spent on products manufactured by companies assessed in this Index.

However, there is no requirement to spend the benefit on nutritious food. For example, a 2016 study found that sweetened beverages were the second-most-purchased item on SNAP benefits, accounting for slightly more than 9% of purchases, while prepared desserts made up 7% of purchases. Moreover, despite the rising number of recipients, many food-insecure households struggle to navigate administrative burdens or lack awareness of eligibility.

The WIC program meanwhile, has a focus on nutrition. The WIC food packages provide supplemental foods designed to meet the special nutritional needs of low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, non-breastfeeding postpartum women, infants and children up to five years of age who are at nutritional risk. Many companies in this Index manufacture such foods. As of 2021, WIC serves 6.2m women and children. However, participation rates in WIC have been declining, largely due to increased barriers for those who would otherwise be eligible, especially during the pandemic, rather than decreasing need.

According to a 2021 study, 21% of US adults experiencing food insecurity were unable to access any assistance at all, while 58% that were enrolled still had difficulty accessing at least one service. The 2022 National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition and Health announced it will make it easier for eligible individuals to access federal food, human services, and health assistance programs such as SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid.

Changes to the Methodology

-

A further shift in focus to commercial approaches for affordability and accessibility, and greater emphasis on improving the price differential between healthy vs. less healthy products.

- For non-commercial activities focused on food donations, greater emphasis is placed on ensuring that these are made responsibly, i.e. being predominantly healthy products.

Key Findings

-

The majority of companies assessed did not show evidence of specifically addressing either the affordability or accessibility of their healthy products in a meaningful way through commercial channels. For those with some form of access and affordability strategy in place, insufficient attention is paid to low-income or food-insecure consumers. No company has such strategies in place across its whole business in the US; actions are confined to specific product lines or brands.

-

However, there are some signs of improvement. Unilever, General Mills, Kellogg, and PepsiCo show they have taken concrete actions to improve the affordability of some of their ‘healthy’ products in the US – more than was the case in 2018. Meanwhile, Unilever, through its Knorr brand, specifically seeks to price some of its ‘healthy’ products appropriately for low-income households, which is a first for this Index.

-

Another first is provided by Campbell, which has started to track the pricing of its products that meet its healthiness criteria against the rest of its portfolio, while also publishing the price differential.

-

Significantly more companies are now publicly committing to addressing the accessibility of healthy products in the US than in 2018. However, the predominant way continues to be through charitable donations – instead of taking a systemic commercial approach to ensure healthier products are widely available at prices also affordable for low-income households. No new commitments or policies to ensure donations are predominantly healthy could be identified, and only a slight improvement was seen in the tracking and evidence of donating predominantly healthy products.

- Kellogg, Coca-Cola, and PepsiCo now show evidence of seeking to improve the commercial distribution and placement of their ‘healthy’ products (or ‘less unhealthy’ alternatives) in low-income neighborhoods, whereas limited evidence of this was found in 2018.

Notable Examples

-

- C

On the website of Unilever’s Knorr brand, the company states: “Make Nutritious Food Accessible & Affordable: Knorr believes that wholesome, nutritious food should be accessible and affordable to all, but unfortunately, that is not a reality for everyone today in America.” Moreover, the company provided robust evidence of how it was seeking to make this a reality – e.g. through conducting appropriate pricing analyses and designing its ‘Better for You’ recipes at affordable price points for low-income consumers [NDA]. The company’s specific attention to low-income consumers is a clear improvement from 2018, when no companies were found to do this.

-

- C

In 2021, Campbell began tracking the average cost per serving of its ‘Nutrition Focused Foods’ against the average cost per serving of the portfolio overall and disclosing the results. It found that these foods cost USD 0.62 per serving on average, compared to USD 0.65 per serving for its entire portfolio. This is the first company in ATNI’s Indexes to do this and publicize it, and the company is well-placed to set SMART targets to improve the price differential further in the future. No other companies were found to track the relative affordability of their products.

C1. Product Pricing

Only Unilever, Campbell, Kellogg, and General Mills were found to make public commitments to address the affordability specifically of their ‘healthy’ foods in the US. Of these, Unilever was the only company to explicitly commit to reaching low-income consumers.

Noteworthy Example: On the website of Unilever’s Knorr brand, the company states: “Make Nutritious Food Accessible & Affordable: Knorr believes that wholesome, nutritious food should be accessible and affordable to all, but unfortunately, that is not a reality for everyone today in America.” Moreover, the company provided robust evidence of how it was seeking to make this a reality – e.g. through conducting appropriate pricing analyses and designing its ‘Better for You’ recipes at affordable price points for low-income consumers. The company’s specific attention to low-income consumers is a clear improvement from 2018, when no companies were found to do this.

General Mills, Kellogg, and PepsiCo were the only other companies to also provide evidence of having a US-specific strategy to improve the affordability of some of their ‘healthy’ products (as defined by the company – see Box 3), although only Kellogg discloses this information publicly. Moreover, each of these only applies these strategies to ‘healthy’ products within specific product categories or brands, rather than across the entire portfolio.

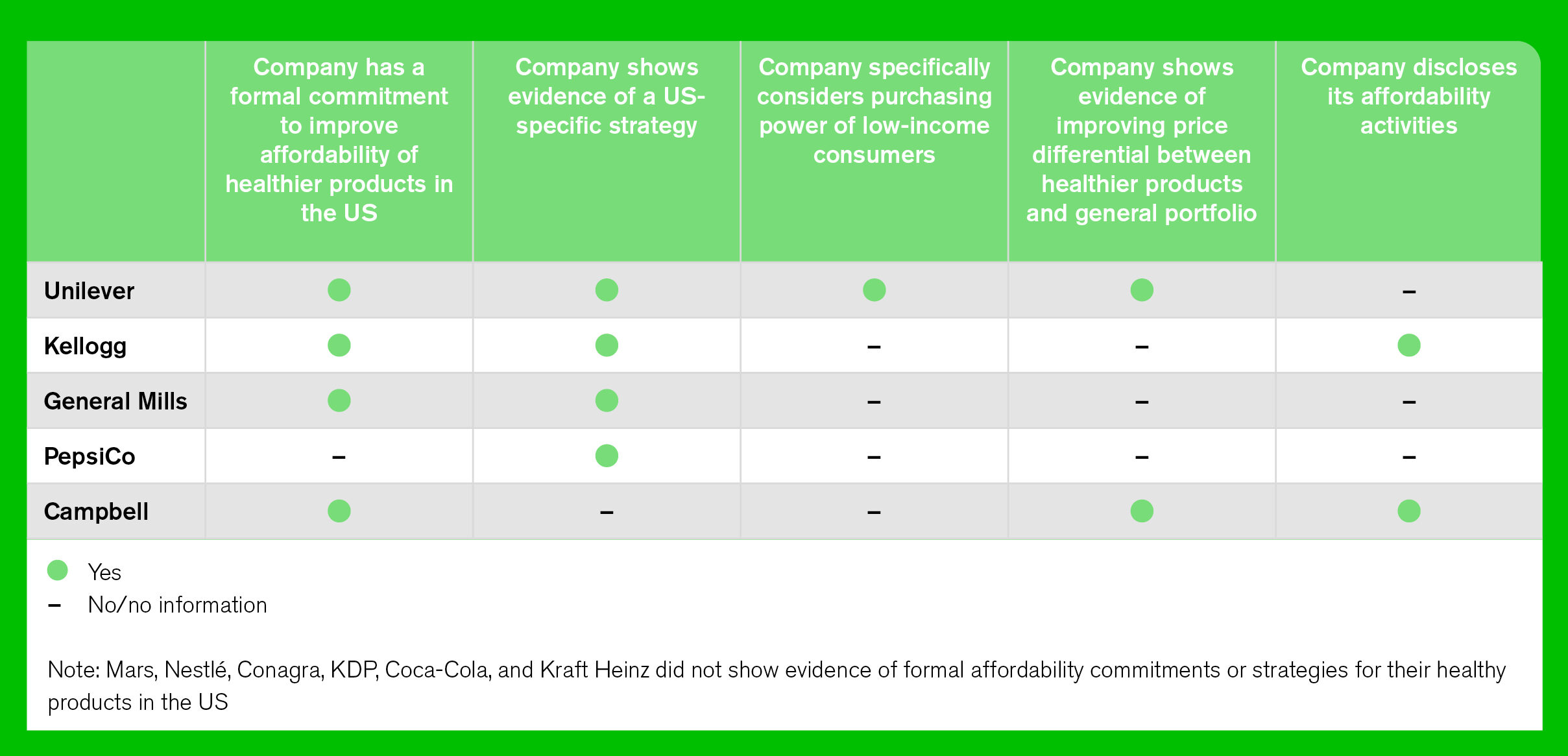

Table 1. Companies’ commitment to improve the affordability of healthy products in the US

However, as in 2018, no companies were found to have defined concrete quantitative targets regarding the affordability of their healthy products, such as improving the price differential between healthy products and general portfolio or achieving a particular price point for ‘healthy’ products for low-income consumers.

Noteworthy Example: In 2021, Campbell began tracking the average cost per serving of its ‘Nutrition Focused Foods’ against the average cost per serving of the portfolio overall, and disclosed the results. It found that these foods cost USD 0.62 per serving on average, compared to USD 0.65 per serving for its entire portfolio. This is the first company in ATNI’s Indexes to do this and publicize it, and the company is well-placed to set SMART targets to improve the price differential further in the future. No other companies were found to track the relative affordability of their products.

-

Six companies did not show clear evidence of seeking to address the affordability specifically of their ‘healthier’ products in the US. These companies are encouraged to adopt formal commitments and develop strategies to do so, perhaps starting with specific product lines or brands.

-

Of the companies with some form of affordability strategies for their ‘healthier’ products in place in place, most could go further by specifically ensuring that such products are affordable for low-income consumers in the US. They could begin by conducting pricing analyses to ensure their ‘healthier’ products are priced appropriately for these groups to afford them.

-

All companies could improve the robustness of their affordability commitments and strategies by developing quantitative targets (with baseline and target year) – such as improving the price differential on ‘healthy’ vs. ‘less healthy’ products within product categories and ensuring that healthier products are less expensive than their less healthy counterparts, or reaching a certain number of low-income consumers with affordably priced healthy products by a set date.

- Nearly all companies are encouraged to improve by disclosing more information on their affordability strategies, to enhance transparency and accountability.

Box 2: Companies' definitions of healthy

As previously mentioned, ATNI’s methodology for Category C considers companies’ affordability and access activities in relation to their ‘healthy’ products, according to the companies’ definition of ‘healthy’. Scores are then adjusted based on a ‘healthy multiplier,’ which uses the results from criterion B3 (which assesses the basic elements, scope and disclosure of a company’s NPM) as a proxy for the quality of the company’s healthy definition, and adjusts the score accordingly. ATNI takes this approach in order to deal with the limitation of companies using different definitions and nutrient thresholds to determine if products are considered ‘healthy’ (or ‘healthier’ alternatives within a product category).

Specifically, companies’ definitions do not always align with internationally recognized definitions of ‘healthy,’ such as the Health Star Rating (HSR) system’s 3.5 threshold.

Kellogg, for example, publishes its affordability and accessibility efforts for its Eggo Waffles brand, most of which achieve HSR scores of 3 stars (less than the 3.5 ‘healthy’ threshold), while some specific products score much lower, such as the Eggo Grab & Go Liège-Style Buttery Maple-Flavored Waffles, which score 1.5 stars. General Mills, meanwhile, states that all its breakfast cereal products qualify as ‘Nutrition Forward Foods’ (the company’s ‘healthy’ definition). ATNI’s Product Profile assessment finds that the sales-weighted mean HSR for the category is 2.6, and only 20% exceed the 3.5-star threshold. In both examples, it is not clear whether the company distinguished between the healthier and less healthy varieties in their access and affordability strategies.

It is, therefore, especially important that companies improve their NPMs and definitions of healthy, and ensure they are benchmarked against internationally recognized systems. This will ensure that their affordability and accessibility strategies are being applied to products that contribute to healthier diets.

C2. Product Distribution

Eight companies were found to have clear commitments to improving the distribution of their ‘healthy’ products to low-income/food-insecure households – a clear improvement over 2018, when only four companies did so. Moreover, nearly all these eight disclose their commitments publicly, whereas only one did so previously. This likely reflects the industry’s recognition of the food security challenges posed by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Campbell’s commitment is of particular note, since it explicitly references the USDA’s definition of food access.

That said, only Kellogg, Coca-Cola, and PepsiCo provided evidence of having a deliberate strategy to address accessibility of ‘healthy’ products (as defined by the company) or ‘less unhealthy’ products through commercial channels; the rest primarily do so through charitable donations. For example, Kellogg and PepsiCo have worked with dollar stores to ensure their cereals (which the companies define as ‘healthy’) and ‘better-for-you snacks’, respectively, are available in stores that are often found in low-income neighborhoods (see Box 4), as well as developing smaller package sizes for healthier products in order to meet the $1 price-point to ensure they are stocked in dollar stories. In the case of Coca-Cola (and to some extent PepsiCo), as part of its participation in the Balance Calories Initiative, the company is working to distribute in low-income neighborhoods with high rates of obesity and display more prominently its reduced-/zero-sugar beverages relative to their full-sugar counterparts (it should be noted that such products likely do not meet ‘healthy’ criteria for the companies; rather, they are ‘less unhealthy’ variants of popular products).

However, as in 2018, no companies were found to have defined concrete quantitative US-specific targets to improve consumers’ ability to access their healthy products – such as the number/percentage of stores in low-income/food-insecure neighborhoods stocking their healthy products, or the number of food-insecure households to reach through improved distribution using USDA definitions and ranges.

Table 2. Companies with commitments, commercial strategies, and philanthropy regarding improving the accessibility of healthy products in the US

While almost all the companies assessed make in-kind donations to the charitable food system, no new commitments or policies were found regarding the responsible donation of products (i.e. to ensure they are predominantly healthy). That said, Kellogg continues to donate both funds and products to a range of hunger-relief organizations such as Feeding America, No Kid Hungry, Action for Healthy Kids, and the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC). It reports that its product donations are aligned with USDA Dietary Guidelines, the only company to do so.

That said, there were improvements by two companies in the tracking of products being donated. For example, Unilever keeps detailed records of its donations by different brands and the approximate proportion of products that comply with its ‘Highest Nutritional Standards’. Meanwhile, General Mills showed evidence that the majority of its product donations meet its internal criteria for ‘Nutrient-Forward Foods.’ However, no company was able to convincingly demonstrate that more than 80% of their product donations met external ‘healthiness’ criteria, such as the HER Nutrition Guidelines, which are based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

-

The increase in the number of companies committing to address access to their ‘healthy’ products is promising. However, the majority of these are encouraged to translate such commitments into commercial strategies and actions to improve the distribution of their healthy products in low-income/food-insecure areas. They are encouraged to work with their distribution and retail partners to make this a reality, rather than focusing predominantly on charitable donations and federal assistance programs.

-

All companies could improve the robustness of their accessibility commitments and strategies by developing quantitative targets (with baseline and target year), such as the number/percentage of stores in food-insecure neighborhoods stocking ‘healthier’ products, or the number of food-insecure households to reach through improved distribution, as defined by USDA definitions and ranges.

- Where philanthropic activities are undertaken to address food insecurity, it is essential that companies adopt policies and tracking systems to ensure these donations are predominantly healthy, to avoid inadvertently exacerbating nutrition issues for the populations they are seeking to help. Companies are encouraged to adopt the HER Nutrition Guidelines for the Charitable Food System, for example.

Box 3: The Role Dollar Stores Play in US Food Security

There are more than 31,000 Dollar General, Dollar Tree, and Family Dollar stores in the U.S., typically situated in low-income areas without grocery stores or supermarkets. A recent study found that 60% of dollar store shoppers come from households with incomes of less than $50,000 a year, and 30% from households with less than $25,000 a year. As such, they are key channels for reaching low-income consumers with affordable products.

However, these retailers have been criticized for crowding out small grocery stores and for selling predominantly unhealthy products, and, in turn, exacerbating obesity and other diet-related diseases among low-income consumers. Manufacturers can help to address this by seeking to ensure that their ‘healthier’ products are available in these stores by developing smaller packages that meet the $1 price-point, ideally at a greater rate that their less healthy products.