Marketing

Responsible marketing policies and auditing of compliance

Category D consists of three criteria:

- D1 Marketing policy: General aspects of responsible marketing

- D2 Marketing policy: Specific arrangements regarding responsible marketing to children, including teens

- D3 Auditing and compliance with policy

To perform well in this category, a company should:

- Establish and implement a responsible marketing policy covering all consumers.

- The marketing policy should be comprehensive in its scope, i.e., considering all media channels, and should embrace the principles of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) general marketing code, as well as the Framework for Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing Communications.

- Commit to substantially increase marketing spending for healthier products relative to the overall marketing budget, including setting quantitative targets for a specified timespan.

- Establish, implement and evaluate a comprehensive policy that explicitly covers responsible marketing practices targeted to children aged 18 years and younger including teens, aged 13-17 years, including all channels and media platforms (i.e., social media, mobile, virtual and marketing communications that use artificial intelligence); locations/settings (i.e., schools grades K to 12 or other places where children gather (YMCA, sports clubs)); child-directed in-store marketing and types of products.

- Make a public pledge to adhere to the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) principles, and further commit to not advertise or market food or beverage products that do not meet the uniform nutrition criteria to children under 18 including teens.

- Commission or participate in external independent audits to assess compliance with marketing policies, as well as disclosure of individual results for all types of channels and media platforms (i.e., digital media or TV).

Ranking

- D1

- Marketing policy

- D2

- Marketing to children

- D3

- Auditing and compliance

The average score on D is 4.2 out of 10. Overall scores are higher for D2 (marketing to children) and D3 (the auditing strategy and policy of companies) than D1 (marketing policy and strategy for all audiences). Mars scores highest in this category, due to its comprehensive auditing efforts, which was also the case for the 2018 US index. General Mills and Kellogg rank second and third scoring 5.1 and 4.8 respectively, closely followed by Nestlé and Unilever (both scoring 4.7).

Category Context

With a marketing budget of nearly $14 billion per year, food, beverage, and restaurant companies in the US exert significant influence over the dietary choices of Americans through the promotion of their products, and is a dominant feature of the food environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently published a report revealing the majority of food marketing promotes predominantly unhealthy products that contribute to malnutrition, and that children continue to be exposed to this. This disproportionate marketing of unhealthy foods is widely recognized as a key driver of unhealthy diets, which in turn, are associated with obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In the US, a robust evidence base shows that children’s and teens’ diet-related preferences and behaviors are influenced by the marketing of unhealthy food and beverage products, which is a driver of poor diet quality, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Corporate marketing practices has led many key stakeholders, including WHO, to call for government and industry to restrict the marketing of unhealthy products, especially to children and teens up to age 17 years.

Industry-supported self-regulatory programs or initiatives have been the primary approach to reduce unhealthy food and beverage marketing to children in the US since 2007. For adult consumers, the gold standard for responsible marketing is the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC’s) truthful advertising and endorsement guidelines, and the ICC Framework for Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing Communications, which sets out general principles governing all marketing communications. It includes separate sections for sales promotion, sponsorship, direct marketing, digital interactive marketing, and environmental marketing. However, ATNI encourages companies to go beyond this, and adopt commitments, concrete targets, and tracking systems to promote their healthier products and variants at a proportionately greater rate than their less healthy products.

Industry self-regulatory programs or initiatives that include the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) and Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU), are administered by the Better Business Bureau (BBB).

CARU addresses how foods (and all products) are advertised to children under 12 years old, accounting for their vulnerabilities by ensuring that advertising directed toward them is truthful, not misleading, unfair, or inappropriate. The Guidelines also reflect the requirements of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998 which prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices in connection with the collection, use, and/or disclosure of personal information from and about children on the Internet.

The CFBAI requires member companies to advertise only food, beverage and meal products that meet CFBAI’s Uniform Nutrition Criteria to children under age 12 years on media covered under the program, or not to advertise any products at all. The program consists of 20 US food and beverage and quick-serve restaurants among its members, including all of the companies assessed in this Index, which together accounted for 74% of advertising on children’s television in the US in 2020. The Uniform Nutrition Criteria were revised in 2018 and implemented in 2020. It should be considered that the nutrition criteria are not as stringent as criteria used in government regulatory policies (e.g., UK, Chile), and these nutrition criteria allow certain products that experts do not recommend for children, such as drinks or foods with high sugar, fat, or sodium content for some categories. It should be noted, however, that WHO defines ‘children’ as those below 18 years old, while a 2015 US Expert Panel advised to include children from birth through age 14. Other recommendations from this expert panel that are still relevant – and not been adopted by CFBAI-participating companies that relate to the marketing definition to include products and brands, audience thresholds for children, marketing settings, and on-pack and in-store marketing (see Box 1).

Box 1. Measuring marketing techniques, the caveats

Food and beverage marketing is a dynamic field that quickly changes based on developments in technology, updated federal and state regulations, and new insights into marketing techniques and opportunities.

ATNI strives to monitor improvements in marketing commitments by food and beverage companies in relation to priority topics in this constantly changing field. Below, we mention some of the nuanced issues that are currently not specifically addressed by the ATNI methodology, as they go beyond data available to the organization:

-

Brands vs. products: The CFBAI has set nutrition criteria for products which meet health standards and are therefore deemed permitted to be advertised to children. Advertising and promotion of products within a brand family that meet the criteria could spill over and affect purchase decisions for other products of the same brand that do not meet such criteria.

-

Making impact: Reformulation strategies – for example, those based on the CFBAI nutrition standards or the Smart Snacks in School program – should be founded on scenario analysis of the highest possible positive health impact based on actual sales and consumption data. This allows for modeling exercises to assess the extent that these foods and beverages will contribute to the improvement of public health. Reformulating products which are widely consumed will have a larger impact on improving public health compared to products which are consumed by a small proportion of the population. However, reformulated products included in the CFBAI only make up a small proportion of the food supply in the US, and thus the impact on providing healthier products on a large scale is limited.

- ‘It’s in the fine print’: All companies have their own tailored marketing policy. Where some policies include an extensive list of the media forms and marketing techniques it entails, others are brief and indistinct. There are many widely established forms of marketing that are excluded from industry self-regulation e.g. child-directed product packaging and in-store marketing, and sponsorships of children’s events/activities. This leaves room for loopholes that enable unhealthy foods to be marketed to children without breaching a company’s policy.

ATNI has started testing the use of tools to extract online retail data, to have more independent performance indicators that will complement the current set of indicators on this topic.

Relevant Changes to the Methodology

- The Category weighting has been reduced by 2.5% points, due the introduction of the Product Profile elements in Category B.

- The methodology is aligned with the updated ICC Framework for Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing Communications, 2019.

- The number of criteria is reduced from six to three, and the number of indicators is reduced from 53 to 33. Also, there is more focus on marketing to children practices, including teens (up to age 18), and efforts that go beyond CFBAI core commitments.

- An ‘age’ multiplier is introduced, to evaluate the extent to which companies’ marketing policies cover both children and teens.

- Auditing and compliance practices are assessed for marketing in both the general population and children.

Key Findings

-

Compared to 2018, when eight (out of 10) companies pledged to support the ICC code, fewer companies (seven out of 11) made such a commitment in this iteration. Four companies go beyond the ICC pledge, demonstrating best industry practices (e.g. to present products in the context of a balanced diet); a slight improvement since 2018, where this commitment was made by three companies.

-

While five companies have made a commitment to increase their marketing spending on healthier products relative to overall marketing spending, none of these companies have set quantitative targets for a specified timespan. As marketing influences purchasing behavior, all companies are encouraged to increase their marketing budgets for the promotion of healthier products and make such commitments public expressed as a percentage of the overall marketing budget as to avoid giving away commercially sensitive information.

-

Since 2018, Mars remains the only company that has commissioned an independent, third-party audit of its marketing compliance to children and all consumers. All companies are recommended to adopt this approach.

-

In 2018, 32 percent of U.S. children and teens (2-19 years) experienced overweight or obesity, and robust evidence links corporate marketing practices to their obesity risk. it is critical that all food and beverage companies responsibly market their products to children, including teens, and follow internationally recognized standards set by WHO, UNICEF and the ICC. Companies must ensure that their commitments, policies and practices are comprehensive and explicitly cover all marketing communication channels and media platforms; locations/settings; and applicable to all products.

-

While all companies commit not to market or advertise their products in primary schools, this commitment is made by just four companies for secondary schools. Only two companies committed not to market in other places where children gather (e.g., YMCAs, after-school clubs, Boys and Girls Clubs, etc). Companies must not market in or near secondary schools, and extend this pledge to other places popular with children.

- While all companies define children as either 12 or 13 years, Unilever has announced it will increase this threshold to 16 years as of 2023 (though this was announced after the assessments for this US index were performed). All companies – and the CFBAI – are strongly encouraged to adopt either the ICC 2018 framework that applies to children, including teens up to 17 years, and the United Nation (UN) definition of a child as up to 18 years old based on the 1989 International Convention on the Rights of a Child.

Notable Examples

-

- D

Out of all companies assessed, Nestlé’s marketing policy is most explicit on what marketing communication techniques it includes (e.g., native online, influencer, and viral), but also on which media it covers (own, third-party, and user-generated media).

-

- D

Unilever made a new commitment not to market their products to children and, in April 2022, also announced that it is raising the age threshold of this commitment to all under 16s – being the first US Index company to use this age limit and the closest to the International Child Rights Convention’s definition of a ‘child’ (18 years).

D1. Marketing policy to all consumers

All companies, with the exception of Kraft Heinz and Campbell, published a policy for responsible marketing to all consumers that is applicable to the US. Six companies’ policies include all forms of marketing embedded within the ATNI methodology (print, broadcast, digital media, point of sale, sponsorship, and other marketing forms), with General Mills, Kellogg, and PepsiCo scoring higher in this regard since 2018.

Seven companies (see Table 1) that pledged to adopt the 2018 ICC Framework for Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing Communications scored highly on marketing policy commitments with regards to fair representation (i.e., marketing should be truthful to the appearance and other characteristics of the product) of their products (for example, on health or nutrition claims and appropriate portion sizes). Kellogg joined Mars, Nestlé, and Unilever to commit to industry’s best practices to not use any models with a body mass index (BMI) of under 18.5 and/or to present products in the context of a balanced diet.

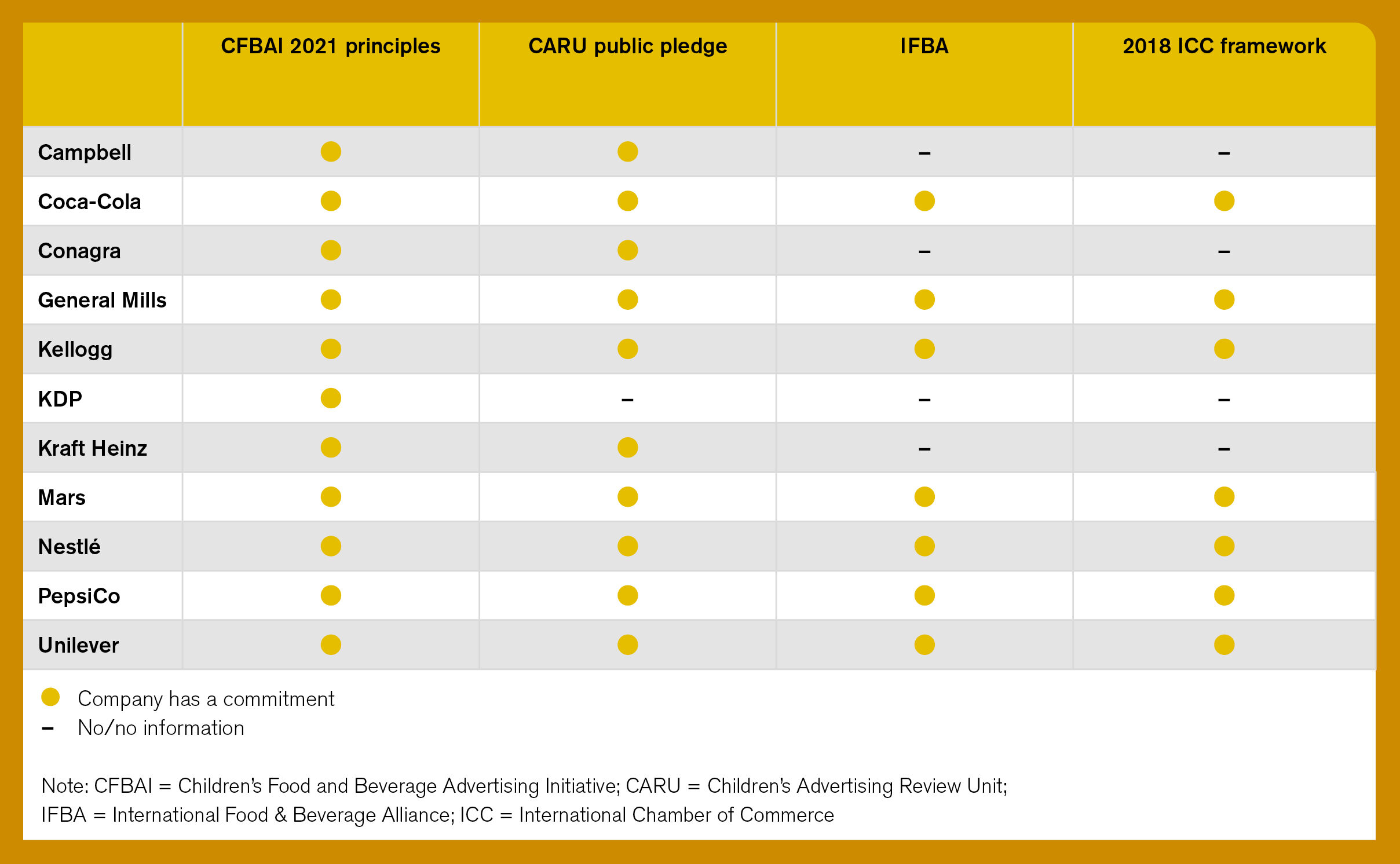

Table 1. Companies’ pledges to commit to international marketing guidelines

Encouragingly, five companies, including Kellogg and Nestlé, commit to proportionately increase their marketing spending on healthier product variants, while PepsiCo and Coca-Cola commit to market their reduced-calorie beverages at a greater rate than full-calorie ones. This is a notable improvement since 2018, when only one company was found to do so. However, none of these companies have set quantitative, time-bound targets for marketing spending to ensure that their healthier products are marketed at a higher rate than less healthy products. Doing so would cement their commitment, and increase accountability to stakeholders.

-

Four companies that have not yet aligned their marketing commitments with minimum standards for responsible marketing, as per the ICC framework, should do so. The ethical guidelines published by the ICC in 2018 are a minimum set of standards to ensure responsible marketing and safeguarding better nutrition for the general audience.

- All companies are encouraged to set quantifiable targets and timelines to increase their marketing of healthy food and beverage products relative to less healthy products in their product portfolios. These firms should be transparent about the criteria used to define ‘healthy’ or ‘healthier’, in order to promote a shift towards healthy eating patterns aligned with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025. These companies are encouraged to track their relative marketing expenditures and publicly disclose their progress.

D2. Responsible Marketing to Children

Nestlé, Mars, Coca-Cola, and Unilever commit not to directly market (a selection of) their products to children (under 12 years in the case of Nestlé, and under 13 years for the other companies). In April 2022, Unilever also announced that, as of 2023, it is raising the age threshold of this commitment to all under 16s – being the first US Index company to use this age limit and the closest to the International Child Rights Convention’s definition of a ‘child’ (18 years). The remaining companies commit to only market products meeting internal ‘healthy’ criteria to children, of which PepsiCo and Coca-Cola increased its age threshold to 13 years. It is also worth noting that the CFBAI will raise the age threshold to 13 years effective 1 January 2023, requiring all participating companies to align with this policy.

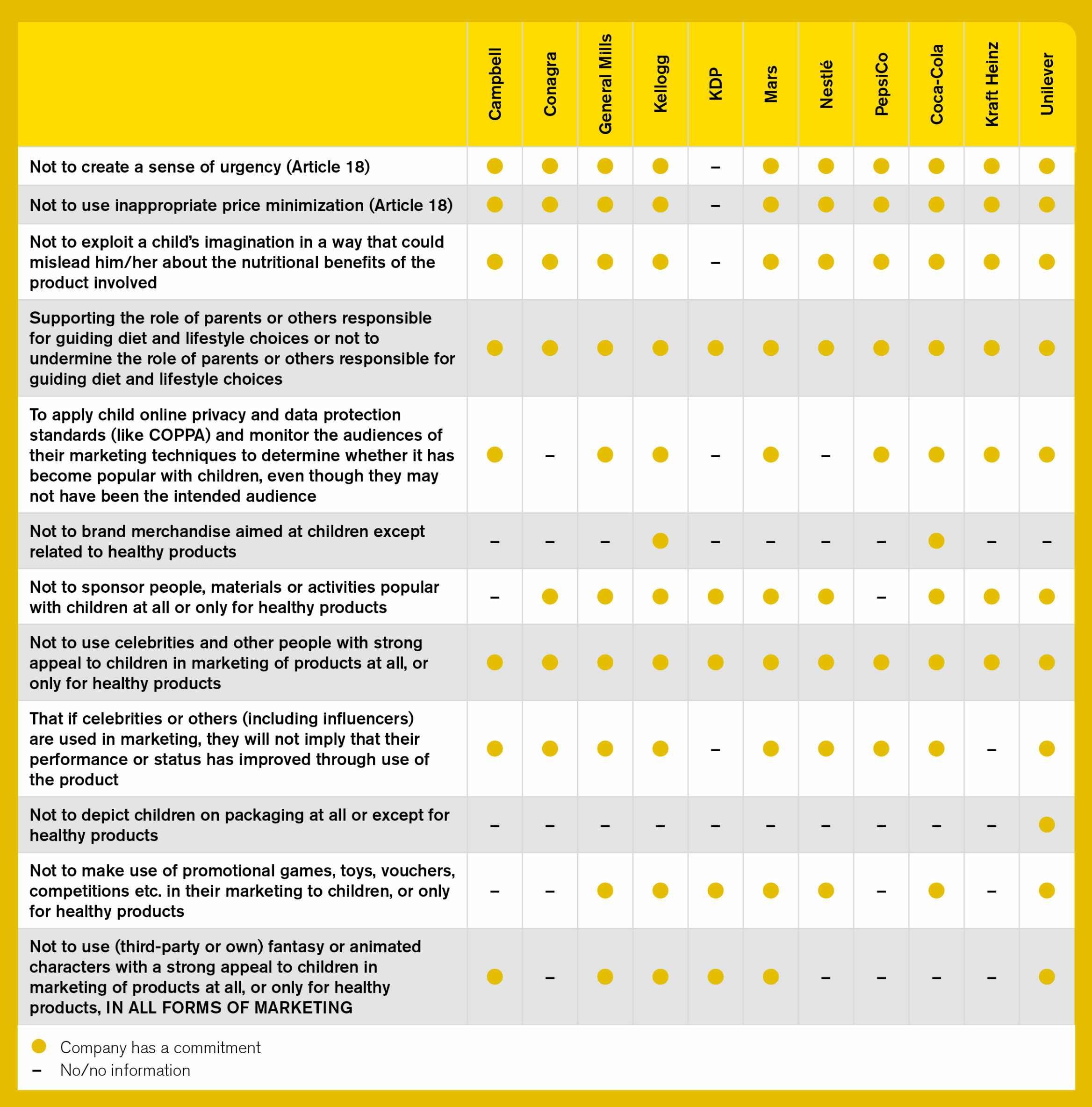

An extensive list of aspirational commitments relating to restricting specific marketing messages and techniques has been assessed, including those related to supporting the role of parents; not creating a sense of urgency; not using celebrities, fantasy, or animated characters; and many more (see Table 2). Kellogg’s and Unilever’s updated policies, closely followed by Mars and General Mills, now capture these commitments most comprehensively in comparison to other companies’ policies, including Nestlé’s, which was the strongest in this regard in 2018.

Table 2. Companies’ commitments for marketing to children techniques and messages

In addition to their own policies regarding marketing to children, all companies commit to following both the CFBAI policy and CARU guidelines, with the exception of KDP (which joined CFBAI in 2019 but is yet to commit to CARU). Consequently, the companies’ policies cover a broad range of marketing media, including print, broadcast, electronic/digital, and other forms, such as cinema, product placements, etc. Beyond this, only Unilever’s policy explicitly includes all in-store or point-of-sales marketing (including packaging); whereas General Mills and Kellogg are the only companies that explicitly include ‘Sponsorship’ (for example, of sporting, entertainment, or cultural events or activities) in their lists.

For restrictions on marketing to children, companies apply an audience threshold for media to determine when the restriction should apply. Most companies apply their marketing restrictions when children make up 30% or more of the audience, as per CFBAI’s updated policy – but best-performing companies (KDP, Unilever, Mars, and Nestlé) go further and apply a threshold of 25% (in-line with the 2015 US Expert Panel (HER) recommendations), where KDP and Unilever have increased their threshold since 2018.

For online marketing, digital tools should be applied to ensure marketing messages do not reach children under the age threshold that companies commit to. All companies report that they review age-related data; ensure the design of their digital websites, pages, social media, or apps do not attract young children; and assess the nature of third-party websites. Some companies go further and also commit to include age-screening prior to logging on/registering or review visitor profiles of third-party websites; Mars and General Mills do both. Where the ICC Framework for Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing Communications specifically addresses digital marketing, comprehensive guidelines on this quickly evolving marketing space should be emphasized and should be taken up by companies and incorporated in their marketing policies (see Box 2).

As in 2018, all companies assessed commit to not market or advertise in primary schools, either for all or only in relation to healthier products. General Mills, Nestlé, Kraft Heinz, and Unilever demonstrate leading practice by also extending this commitment to secondary schools – a clear improvement since 2018, when only General Mills and Kraft Heinz did so. Moreover, Unilever and Coca-Cola now extend their responsible marketing commitments to other places where children gather alongside Nestlé, which was the only company to do so in 2018.

-

While ATNI acknowledges that companies are slowly moving in the right direction, they are encouraged to further increase the age threshold for their marketing restrictions to 18 years, as recommended by UN agencies including WHO and UNICEF, to ensure all children (including teens and adolescents) are sufficiently safeguarded from the marketing of unhealthy products. Also, an audience threshold of 25% should be adopted by all companies.

-

ATNI recommends all companies commit not to market to children at all.

-

Companies are encouraged to extend their marketing restrictions to fully cover the school environment, including secondary schools, and other places where children, including teens, typically gather.

- To enhance transparency and accountability, companies should be as explicit and comprehensive as possible in describing the forms of marketing and media their policy applies to. This is especially the case for digital marketing, giving that this is a rapidly evolving field, and it cannot be taken for granted that companies and other stakeholders have the same definitions of terms such as ‘all media’, for example.

Box 2: Digital Marketing to Children

The proliferation of marketing techniques through digital media has caused alarm among concerned stakeholders. Children are a particularly vulnerable demographic in the digital marketing sector, as they are targeted by marketing techniques that exploit how they use the Internet for social networking, video-sharing, gaming, etc. Despite being ‘digital natives’, research shows that only a minority of children can identify sponsored content. For example, 24% of children aged eight to 11, and 38% of those aged 12 to 15, can correctly identify sponsored search links on Google. Stakeholders’ fears around digital marketing to children are compounded further by the increase in screen-time and online learning that resulted from COVID-19 restrictions. Out of all companies assessed, Nestlé’s marketing policy is most explicit on what marketing communication techniques it includes (e.g., native online, influencer, and viral), but also on which media it covers (own, third-party, and user-generated media).

D3. Auditing and Compliance

All 11 companies are subject to annual CFBAI audits of their compliance with marketing to children policies, which monitor their advertisements on child-directed TV, print, radio, the internet (including company-owned websites, third-party websites, and child-directed YouTube channels), and mobile apps in the US, as well as a self-assessment report. However, not only does this not cover the full range of media their policies apply to, but it also does not cover their responsible marketing policies for the general audience.

Mars is the only company who hires an independent external auditor unrelated to an industry association and performs an audit of their marketing policy for both the general audience and children. Their audit covers all media specified in the policy: Not just TV and digital media, but also publishing, social media, and posters/billboards.

According to the latest CFBAI Audit report, it found “excellent compliance” in 2020, and there were “very few occasions when foods that did not meet CFBAI’s Uniform Criteria were advertised to children in covered media”.

For other channels, such as television, digital, and mobile (including company-owned websites, in-app advertising, and child-directed YouTube channels), some instances of non-compliance were found. The report provides commentary on these, naming the companies involved and the steps taken to rectify their actions – although it is not clear if this constitutes a comprehensive list of instances of non-compliance, or are just some indicative examples.

It is important that companies also disclose information about their individual audits and their findings on their own domains. Only three companies (General Mills, Kellogg, and KDP) were found to publish the CFBAI results on their own website, although this is an improvement since 2018, when it was only PepsiCo. Mars, meanwhile, only publishes its compliance levels for specific media at a global level, and overall compliance at regional levels (e.g. ‘North America’); it is not specific about its compliance in the US market, nor by media type.

It should be noted, however, whether it is performed by an industry-led organization such as CFBAI or an external auditor (independent from industry), its credibility is only as valid as the quality and comprehensiveness of the policy it assesses. An audit of a weak marketing policy will not add much weight to the credibility of the marketing policy.

Seven companies (General Mills, Kellogg, Mars, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, and Unilever) now report their response mechanisms for instances of non-compliance, whereas only Mars did so in 2018. ATNI found some of these response mechanisms to be more structured and robust: General Mills, for example, deals with issues of non-compliance through its Responsible Marketing Council, commissioning training where necessary as part of the remediation. The CFBAI auditing report also provides numerous examples of actions taken by specific companies to remedy issues of non-compliance. Generally, most companies report that, due to a low number of such instances, the corrective action taken is always specific to the case at hand, rather than a systematic approach.

-

Companies are encouraged to audit their full marketing policy and be more transparent about their auditing results, providing both quantitative and qualitative information for specific media and marketing forms in their reporting/websites.

-

All companies should ensure they have robust corrective mechanisms in place for when instances of non-compliance are found, and that these are publicly disclosed.

- Category D1and D2 relate to establishing and implementing a marketing policy to cover all consumers and children respectively and having strong and solid policies in place are essential before auditing and compliance measures are performed. All companies should primarily focus on establishing comprehensive marketing policies especially for children, including teens, as not having those in place makes auditing and compliance measures less relevant

Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes

Nutrition is particularly important within the first 1,000 days of a child’s life (from conception to age two).

Optimal breastfeeding is a crucial element of infant and young child nutrition. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that infants everywhere be breastfed exclusively for the first six months, at which point safe, appropriate complementary food (CF) should be introduced to meet their evolving nutritional requirements. The WHO also notes that CF should not be used as breast-milk substitutes (BMS), and that infants and young children should continue to be breastfed until they are aged two or older (WHO, 2003).

Breastfeeding has long been proven to provide myriad significant health benefits compared to baby formula. These benefits are unique to breastfeeding and help both mother and infant (Chowdhury et al., 2015; Sankar et al., 2015). Positive long-term benefits for infants include protection against becoming overweight or obese, as well as against certain non-communicable diseases such as diabetes mellitus (Victora et al., 2016).

However, several factors, including employment, that are not supportive of breastfeeding, may influence women’s and parents’ choices of resorting to formula milk instead of breastfeeding (WHO and UNICEF, 2022). Formula milk has its place for women and parents who unable or do not want to breastfeed, often the result of other factors – such as employment – that are not supportive of breastfeeding.

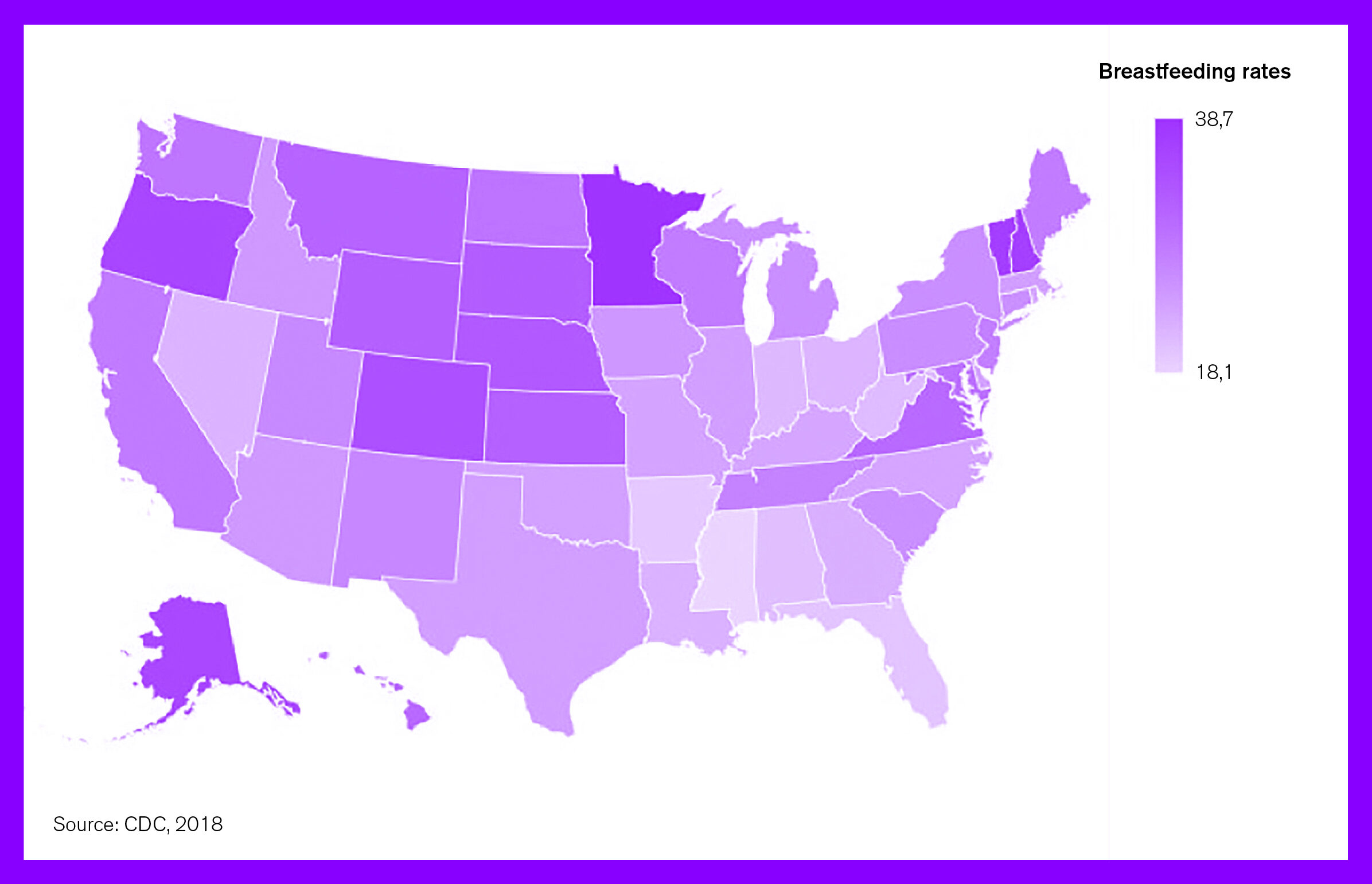

In the United States, according to national figures from the National Immunization Survey (NIS) 2011-2018, 25% of infants in 2018 were exclusively breastfed through six months compared to 18.8% in 2011. As seen in Figure 1, breastfeeding rates through six months vary from state to state, with no single state in 2017 having breastfeeding rates higher than 38.1%. Further, 83.9% of infants were ever-breastfed in 2018, compared to 79.2% in 2011. Rates of exclusive breastfeeding through three months also rose from 40.7% in 2011 to 46.3% in 2018. The percentage of breastfeeding was lower among infants aged 12 months, but increased between 2011 and 2018 (from 26.7% to 35%) (CDC, 2018). Despite increases in breastfeeding in the recent years, figures still fall short of the World Health Assembly (WHA) global target of at least 50% of infants under six months of age to be exclusively breastfed by 2025 (WHA, 2018).

According to the national figures in 2018, supplementation with infant formula before two days was 19%, 31% before three months; and 35.8% before six months (CDC, 2018).

The US Breastfeeding Committee has shared comprehensive policy solutions to address the infant formula shortage, with the following actions outlined to support breastfeeding and ensure infant nutrition security:

-

Establish a national paid family and medical leave program. The FAMILY Act (S. 248/H.R. 804) would ensure that families have time to recover from childbirth and establish a strong breastfeeding relationship before returning to work.

-

Ensure all breastfeeding workers have time and space to pump during the workday. The Providing Urgent Maternal Protections (PUMP) Act (S. 1658/H.R. 3110) would close gaps in the Break Time for Nursing Mothers Law, giving nine million more workers time and space to pump.

-

Invest in the CDC Hospitals Promoting Breastfeeding program by increasing funding to $20M in FY2023. This funding helps families start and continue breastfeeding through maternity care practice improvements and community and workplace support programs.

- Create a formal plan for infant and young child feeding in emergencies. The DEMAND Act (S. 3601/H.R. 6555) would ensure the Federal Emergency Management Agency can better support access to lactation support and supplies during disasters.

Figure 1. Breastfeeding rates through six months among infants born in 2017 by state

The International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes is a global health policy framework developed by WHO in 1981 to regulate the marketing of breast-milk substitutes in order to protect breastfeeding. Since 1981, 18 WHA resolutions have been adopted to clarify and extend the requirements of the International Code (WHO, 2020). The International Code, along with all subsequent relevant WHA resolutions, are considered together and are hereinafter collectively referred to as ‘the Code’.

According to the Code, breast-milk substitutes are any milks, both in powdered and liquid form, which are specifically marketed for feeding infants and young children up to the age of three. BMS products therefore include infant formula (intended for infants aged zero to six months), follow-up formula (intended for older infants between six and 12 months), and growing-up milks (intended for young children aged 12-36 months and also known as toddler milks in the US), and all formulas for special medical purposes (intended for infants and young children aged 0-36 months). Other BMS products include foods and beverages promoted as being suitable for feeding a baby during the first six months of life, including baby teas, juices, and waters, as well as feeding bottles and teats (WHO, 2017). All provisions of the Code apply to all types of BMS, which cover, inter alia, restrictions on the advertising, point-of-sale promotion, and marketing of the products within healthcare facilities, as well as required information on product labels around the appropriate use of BMS. The guidance associated with WHA 69.9 also saw requirements introduced in 2016 concerning the marketing of complementary foods (intended for older infants and young children between six to 36 months of age) of appropriate nutritional quality.

Although the Code is not legally binding, it is expected that governments “take action to give effect to the principles and aim of this Code, as appropriate to their social and legislative framework, including the adoption of national legislation, regulation or other suitable measures” (Sub-article 11.1 of the Code) (WHO, 2020). The United States did not ratify the original Code in 1981 and is one of the few countries not to have adopted any Code provisions (WHO, 2022a).

While the government has a responsibility to fully implement the Code in national legislation, the Code states that “independently of any other measures taken for implementation of the Code, manufacturers and distributors of products within the scope of the Code should regard themselves as responsible for monitoring their marketing practices according to the principles and aim of this Code, and for taking steps to ensure that their conduct at every level conforms to them” (Sub-article 11.3 of the Code) (WHO, 2020).

Abbott, Reckitt, and Nestlé are the largest players in the baby food market: Together, they account for nearly 72% of the total baby food market share and for 89% of breast-milk substitutes alone. The most prominent brands are Enfamil (Reckitt), Similac (Abbott), and Gerber (Nestlé): Combined, they have 65% of the total baby food market in the United States (Euromonitor, 2021). Most recent data shows that, in 2021, 35% of Reckitt’s, 45% of Abbott’s, and 11% of Nestlé’s food baby global sales were attributed to sales in the US.

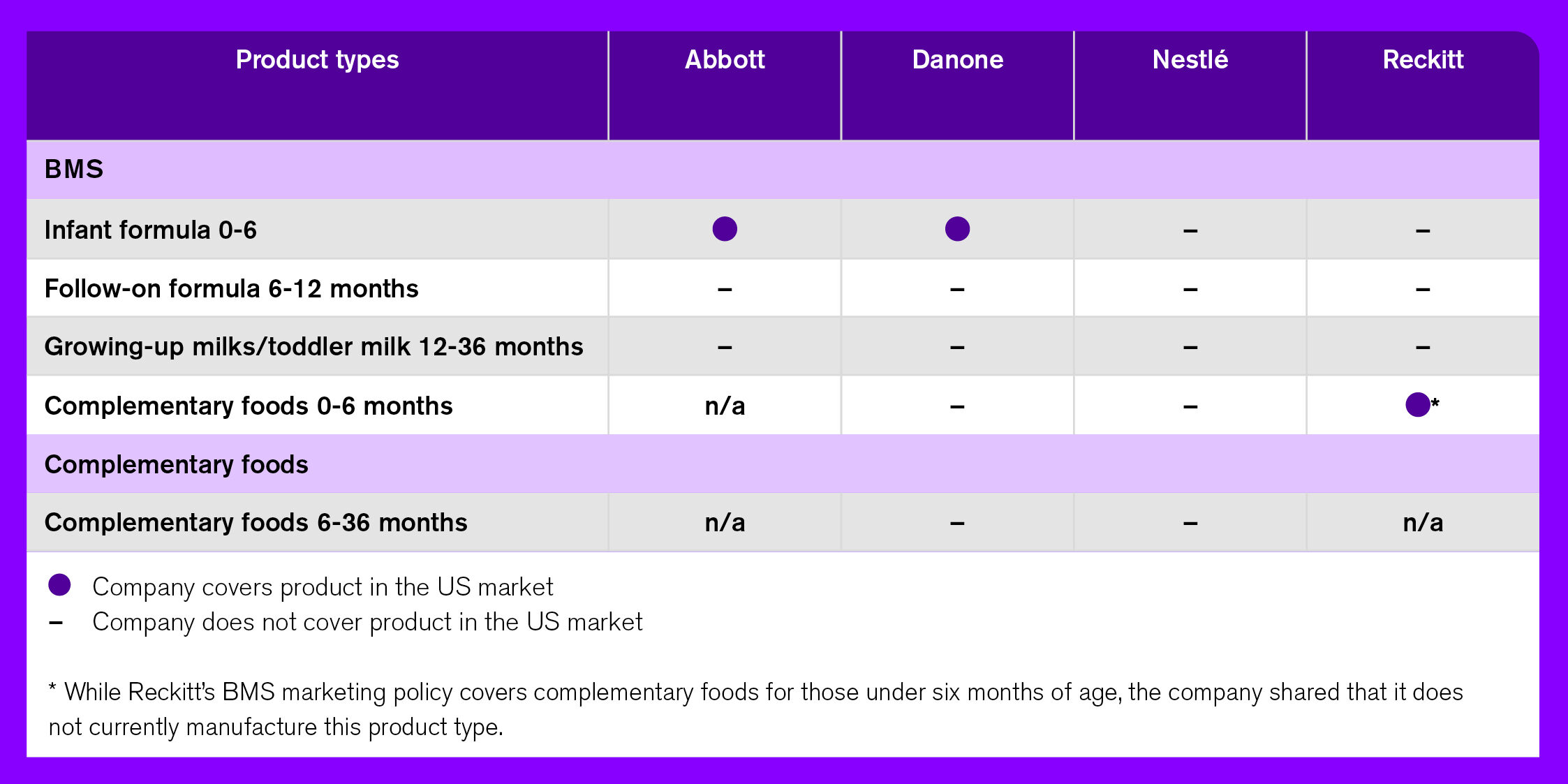

Among the companies assessed in ATNI’s 2021 BMS/CF Marketing Index, Abbott, Danone, Nestlé, and Reckitt were reviewed on their BMS market in the United States. Danone and Nestlé were also assessed on complementary foods. The following section describes these companies’ policies and how they are applied in the US, based on the 2021 BMS/CF Marketing Index assessments.

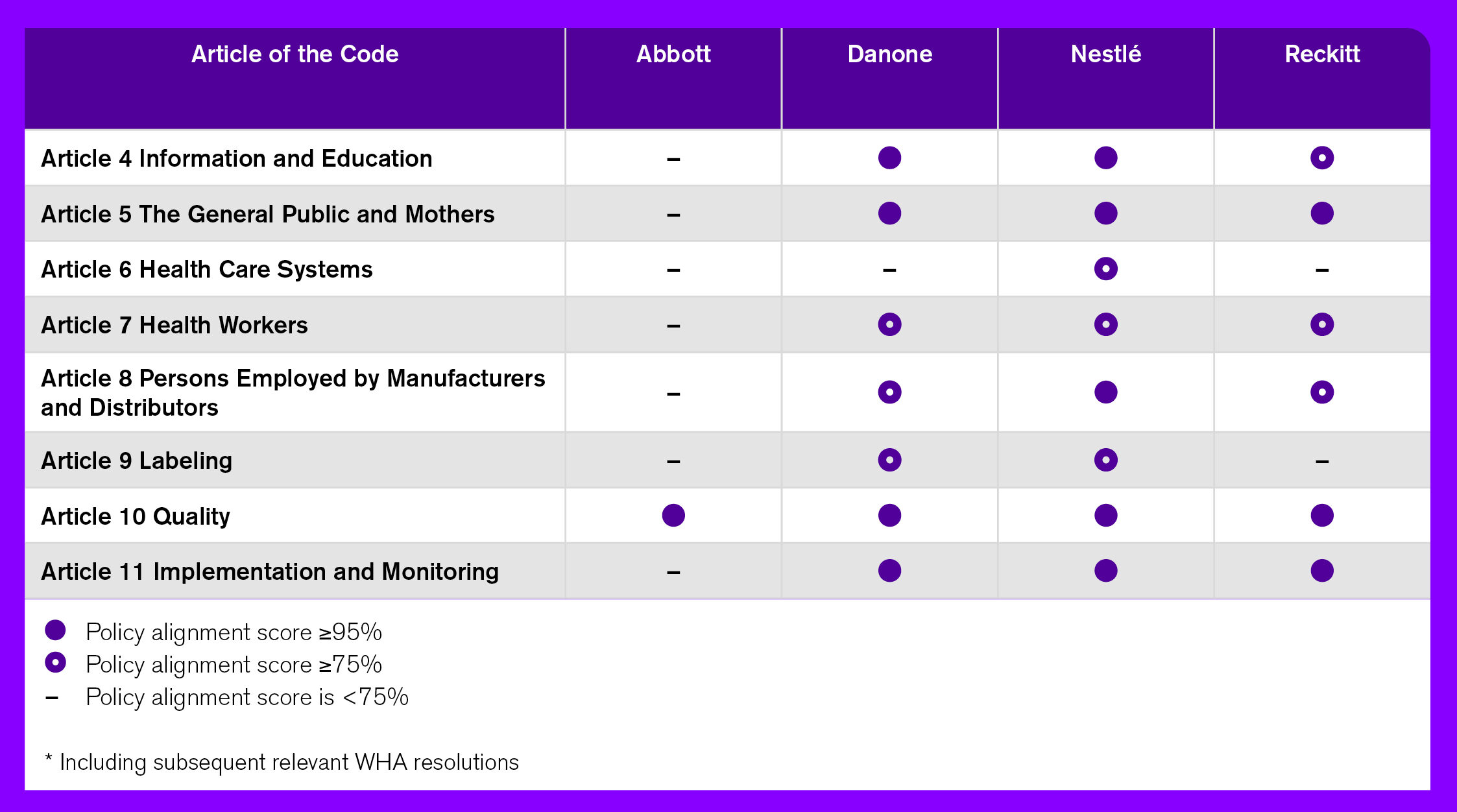

Each of the four companies has at least one policy addressing the marketing of breast-milk substitutes. However, neither Danone nor Nestlé was found to have a policy on the marketing of complementary foods. Table 3, below, provides an overview of each company’s commitments around BMS marketing, and their level of alignment to the provisions of the Code. Among the four companies, Abbott has relatively weak commitments in alignment with the Code, whereas those of the remaining three vary across different forms of marketing.

Table 3. Alignment of companies’ BMS marketing policies to the Code

As shown in Table 4, despite the companies having policies around the marketing of breast-milk substitutes, the commitments outlined do not apply in the US as it is classified as a ‘lower-risk’ country. However, this is an exception in the case of Abbott and Danone, which universally uphold their BMS marketing commitments even in countries where local Code regulations are absent or less stringent than their own policies – although this is only in relation to their infant formula products intended for infants under six months of age. Abbott’s commitment to upholding its BMS marketing policy for infant formula globally is new; however, this updated policy (dating May 2020) has been found to be less aligned with the Code compared to the assessment of the company’s prior policy in the 2018 Index. Nestlé, on the other hand, committed in its public response to the BMS Call to Action to unilaterally stop the promotion of infant formula for infants 0-6 months of age in all markets by the end of 2022, and outlined in its roadmap the company’s plan to explicitly extend its policy to the US, where Code regulations are absent. With regards to follow-up formula (6-12 months), the companies only uphold their BMS marketing commitments in ‘higher-risk’ countries – while Reckitt and Nestlé (at the time of the 2021 BMS/CF Marketing Index assessment) similarly do so for their infant formula (0-6 months) products.

Table 4. Companies’ marketing commitments as applicable to its products in the US market

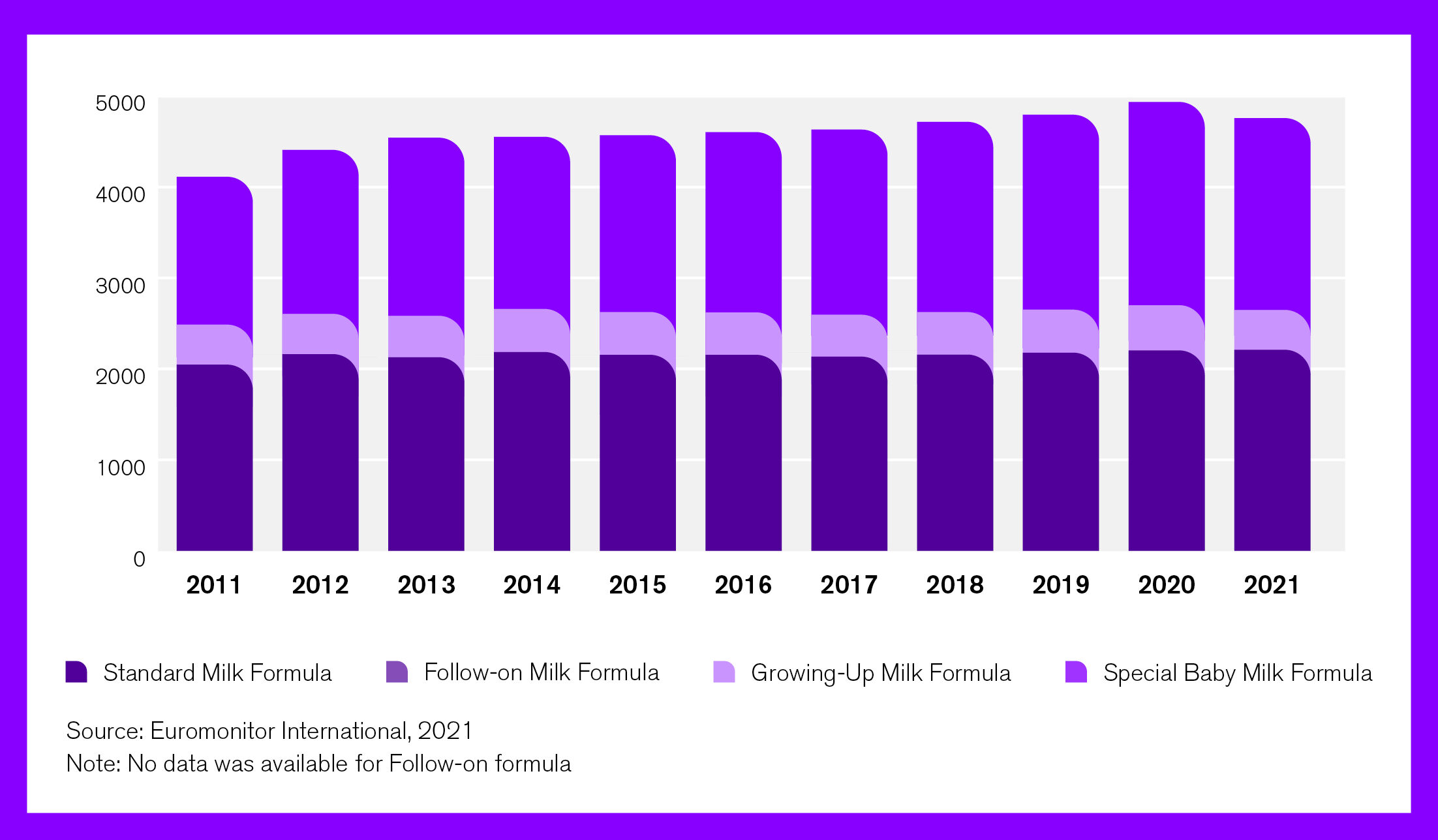

No commitments are applied in any market, however, to the marketing of growing-up milks (aka toddler milks) or complementary foods. As shown in Figure 2, baby food sales have increased in the past 10 years. Among all, a larger increase is seen in complementary foods, followed by formulas for special medical purposes.

Figure 2. Growth of sales of baby food by category in the US 2011-2021 (USD million)

Data on advertising spending suggests that toddler milks are being increasingly promoted in the US, while infant formula advertising is declining. Concerns over the marketing of toddler milk include confusing caregivers between the types of milk formulas intended for different age groups, and promoting products with misleading claims while their nutritional quality is problematic (Harris and Pomeranz, 2020). The American Academy of Family Physicians has noted the additional cost of toddler milks and that these products have no proven advantages over whole milk (O’Connor, 2009) – particularly as research shows toddler milks contain more sodium and less protein than whole cow’s milk, and the added sugars in toddler milks are not recommended for young children’s consumption (Vos et al., 2017).

There are similar concerns over the nutritional quality and thus marketing of CFs, as research has shown that most CFs sold in the US contain added sugars and have high levels of sodium (Maalouf et al., 2017). Furthermore, in 2016-2018, nearly one in three (32%) US infants was introduced to complementary foods before the age of four months, with 51% being introduced at 4-6 months. A higher prevalence of early introduction was seen among Black infants and infants of lower socioeconomic status (Chiang et al., 2020).

A study by Pomeranz et al. (2021) found several promotions in the form of coupons, discounts, rewards, and direct contact on the US websites of Enfamil (MeadJohnson), Similac (Abbott), and Gerber (Nestlé) (in decreased order of findings). Among the three brand websites, Similac’s infant feeding content was found to have more mentions of negative breastfeeding issues relative to positive breastfeeding mentions, followed by Enfamil. Such marketing practices could discourage breastfeeding and encourage the use of infant formula (Pomeranz et al., 2021). The WHO report published this year on the scope and impact of digital marketing in promoting breast-milk substitutes found that BMS brand accounts were highly active on social media in the United States. The research also found that BMS brand accounts published content about breastfeeding in addition to content about their own brand and products. Therefore, mothers who search for information about breastfeeding are likely to be exposed to content that directs them towards a BMS brand (WHO, 2022b). Apart from online and digital marketing, research has shown that other marketing techniques prohibited under the Code are common in the United States, including products labeled with inappropriate messages and claims, and promotions throughout the healthcare system, such as free samples offered in hospital discharge packs, which has been shown to be associated with lower breastfeeding rates (Harris and Pomeranz, 2020).

The 2022 status report on the national implementation of the Code reveals that, to date, the United States continues to not have any legal measures related to the Code (WHO, 2022a). Coupled with the fact that studies show BMS marketing is prevalent in various forms in the country, the role of companies in ensuring their practices are Code-aligned is paramount. To do so, BMS and CF manufacturers are urged to fully align their policies and practices with the provisions of the Code, apply the Code provisions in all markets they sell their baby food products in (with no distinction between higher- and lower-risk markets as every child has the right to optimal health, and in relation to all products covered by the Code), and to uphold those commitments irrespective of whether national regulations are absent or weaker than the company’s policy.

ATNI has developed a model company policy which consolidates the provisions of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes adopted in 1981, along with the subsequent WHA resolutions, to guide manufacturers in responsible BMS marketing that is fully aligned with the Code.