Engagement

Influencing governments and policymakers and stakeholder engagement

Category G consists of two criteria:

- G1 Lobbying Policymakers and Government Bodies

- G2 Stakeholder Engagement

To perform well in this category, companies should:

- Establish effective management systems for governing lobbying activities, such as board oversight, audits, and regular reviews of trade association memberships.

- Show evidence of lobbying in support of government policies to address malnutrition (including obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs)) and public health in the US.

- Disclose lobbying activities and positions relating to nutrition issues, membership of and financial support for industry associations, spending on lobbyists, and political donations.

- Show evidence of engaging a wide range of stakeholders in developing/updating their nutrition-related strategy, policies, and other activities.

- Disclose examples of nutrition-related stakeholder engagement, and how this has been used to adapt their nutrition-related strategy, policies, and other activities.

Ranking

- G1

- Influencing policymakers

- G2

- Stakeholder engagement

PepsiCo and Unilever achieve the highest scores of 5.8, demonstrating strong disclosure of lobbying expenditures and lobbying positions respectively. They also perform well on nutrition-related stakeholder engagement. Overall, companies showed improvement in Category G, the average score increasing from 3.5 to 4.4, with more companies disclosing information relating to lobbying and demonstrating more examples of nutrition-related stakeholder engagement.

Category Context

Government regulation plays a key role in changing the food environment and addressing public health challenges, including addressing obesity and diet-related NCDs. While these come in many different forms, the World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted a range of priorities for governments, including fiscal measures to address obesity (such as taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), regulatory restrictions on marketing unhealthy products (to children), and increased front-of-pack (FOP) labeling requirements).

Some countries already have such policies in place. In the US, proposals have been made, but faced significant opposition – including from industry actors. For example, in recent years, the American Beverage Association (ABA) has lobbied against SSB taxes at the federal level, as well as in California and other West Coast states. This is despite growing evidence of the effectiveness of such taxes, including from within the US: Philadelphia’s tax on SSBs has led to a fall in sales of such beverages since 2017, although it is currently in danger of being repealed. Meanwhile mandatory FOP labeling has resurged on the agenda recently, with a taskforce of 26 food and health experts recommending the FDA develop a FOP labeling plan, and the Congressional Democrats introduced a bill that would require the FDA to create standardized, front-of-package labeling for all food that has a nutrition label.

Given that such policies directly impact companies, these, too, have the right to be heard during the policymaking process. In the short run, such policies could bestow companies that are ahead of the curve on aspects of nutrition (such as formulation, marketing, or labeling) with a competitive advantage. Meanwhile, this would demonstrate their commitment to supporting public health, reducing reputational risk, and enhancing relationships with stakeholders – especially investors who are increasingly paying attention to companies’ lobbying activities and the risks involved.

Yet the risk that companies and their trade associations will lobby to promote interests inconsistent with the wider public health interest is well-documented. It is therefore essential that companies conduct such lobbying activities responsibly, proportionately, with effective management systems in place, and with transparency – or not at all. To help facilitate this, ATNI was involved in developing the Responsible Lobbying Framework, which was launched in 2020: a free, sector-agnostic tool that sets out globally applicable principles, standards, and practical steps to ensure lobbying is conducted responsibly and serves the public interest. While the US has some of the most detailed lobbying disclosure requirements, by way of the Lobbying Disclosure Act, there are nevertheless many ways that companies can go beyond these to demonstrate their commitment to transparency and adequately facilitate scrutiny from stakeholders.

It is essential that companies – when designing, implementing, reviewing, and/or updating their nutrition-related strategies, policies, and other nutrition-related activities – engage with external stakeholders with established expertise and/or groups representing those particularly affected by the companies’ products and practices (especially vulnerable groups) – they not only enhance their accountability to such stakeholders, but their insights can ensure that nutrition-related activities are sufficiently aligned with the public health interest. The AccountAbility AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard offers a best practice framework for assessing, designing, implementing and communicating the quality of stakeholder engagement.

It is also essential that companies are as transparent about such stakeholder engagement, being specific about whom they engaged (either on an individual level or the organizational affiliations), how they engaged, which topics were discussed, and what the outcomes were. While confidentiality is sometimes necessary to allow individuals to speak freely, companies should seek to disclose as much as possible with the consent of the relevant stakeholders. Moreover, anything that might generate a conflict of interest should also be disclosed, such as whether any compensation was involved. This transparency enables other stakeholders to determine for themselves the legitimacy of such engagement.

Relevant changes in the methodology

-

New indicator on management systems for lobbying, derived from the Responsible Lobbying Framework

-

More weight on examples of lobbying in support of policy measures in the public health interest

-

More detailed indicators regarding trade association memberships, political expenditures, and lobbying disclosure

-

Greater alignment with the AccountAbility AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard, as well as more emphasis on transparency regarding stakeholder engagement

- Indicator on quality of partnerships and third-party leadership for non-commercial consumer education and healthy eating programs (moved from E3).

Key Findings

-

While some companies provided examples of lobbying in support of government policies to address malnutrition in the US, none indicated that they had advocated for or lobbied in support of key WHO-endorsed policies – such as fiscal measures to address obesity, marketing restrictions for unhealthy products, or enhanced FOP labeling requirements – either at the federal, state, or municipal level – in the last three years.

-

Most companies were very transparent about their political contributions (incl. via political action committees (PACs)) on their own domains and provide links to the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) registries. However, very few go beyond mandatory disclosure on lobbying registries and are transparent about their state-level lobbying activity, the identities of lobbyists and lobbying firms they use, and the amounts they spend on lobbying in the US on their own domain. That said, PepsiCo’s disclosure was found to be the most comprehensive in this regard.

-

Most companies could also improve the comprehensiveness of their disclosure of trade association memberships, as well as disclosing the amount of membership dues spent on lobbying and any board seats they hold at these organizations, on their own domains.

-

Clear disclosure regarding the companies’ lobbying positions on important nutrition-related public health policies remains limited. That said, Unilever provides a positive example that other companies can seek to emulate, by providing details on when it would and would not support a range of policies.

-

Encouragingly, all companies demonstrated some evidence of engaging with nutrition-related stakeholders in the US, the majority providing a wide range of examples and types: a noticeable improvement since 2018. Around half the companies demonstrated that they had done so specifically in relation to multiple different elements of their nutrition strategy and/or activities, engaging in direct, one-to-one consultations.

- Nevertheless, disclosure regarding stakeholder engagement lagged significantly behind performance. Companies were frequently vague in their public reporting as to which precise organizations or individuals they engaged, which topics were discussed, and what the outcomes of the engagement were. Moreover, information regarding any compensation involved was largely absent. Together, this prevents external scrutiny of the quality and legitimacy of the stakeholder engagements the companies have carried out.

Notable Examples

-

- G

KDP reports that it engages with external, credentialed experts in public health, nutrition, fitness, mindfulness, and academia, as well as the Partnership for Healthier America and other public health-oriented civil society organizations, to help shape its nutrition-related activities. This includes the development of its ‘Positive Hydration’ strategy and discussing the marketing of its beverages.

-

- G

General Mills provides hyperlinks directly to several of its policy consultation comments and letters to policymakers on its website, a practice also demonstrated by the Sustainable Food Policy Alliance.

-

- G

Unilever publishes a relatively comprehensive range of ‘Advocacy and Policy Asks’ on its website. Moreover, in its ‘Position on Sugar’ and ‘Position on Nutrition Labeling’ documents, the company provides additional detail, publicly specifying under which conditions the company would support (or not support) certain policies.

-

- G

PepsiCo highlighted its lobbying efforts with the ABA and state-level trade associations in support of legislation in Chicago, New York City, and Ohio to support healthier ‘default’ beverage options for children’s meals at restaurants, an acknowledged intervention to help address childhood obesity.

-

- G

Nestlé states that it regularly reviews its memberships and that it will withdraw if “Nestlé is regularly in opposition with the positions/agendas of the organization (this includes inappropriate lobbying practices); the organization has not delivered the outcome expected for many years; weak governance putting at risk Nestlé’s reputation; [or] the evolution of the membership of the organization is not in alignment with Nestlé’s agenda, values, and principles.”

G1. Responsible Lobbying

Encouragingly, all but three companies have assigned to their board oversight of their lobbying policy, positions, and practices. Moreover, all but three state that they conduct regular reviews of their trade association memberships to monitor their public policy positions and activities, and ensure alignment with the company’s policies and/or positions.

Notable Example: Nestlé states that it regularly reviews its memberships and that it will withdraw if “Nestlé is regularly in opposition with the positions/agendas of the organization (this includes inappropriate lobbying practices); the organization has not delivered the outcome expected for many years; weak governance putting at risk Nestlé’s reputation; [or] the evolution of the membership of the organization is not in alignment with Nestlé’s agenda, values, and principles.” For example, at the end of 2017, the company withdrew from the Grocery Manufacturers Association (see Box 1).

However, only two companies were found to carry out internal audits of their lobbying activities and disclosure: General Mills indicates that it audits compliance with its Civic Policy and the accuracy of its disclosure, while Kraft Heinz “partners with outside counsel to conduct an internal audit of all lobbying practices and reporting.”

Six companies (Mars, Unilever, Nestlé, General Mills, Kellogg, and PepsiCo) provided evidence of supporting policies to address malnutrition (incl. obesity and diet-related NCDs) and public health in the US in the last three years.

Notable Example: PepsiCo highlighted its lobbying efforts with the ABA (American Beverage Association) and state-level trade associations in support of legislation in Chicago, New York City, and Ohio to support healthier ‘default’ beverage options for children’s meals at restaurants, an acknowledged intervention to help address childhood obesity. Moreover, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, most companies were active in advocating for increased flexibilities in USDA food and nutrition programs to extend access to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), school lunch and breakfast programs, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) for food-insecure families and children. It should be noted that sales of products through these programs comprise substantial revenues for food and beverage manufacturers.

Companies did not provide any clear examples of lobbying in support of fiscal measures to address obesity, regulatory restrictions on marketing/advertising unhealthy products (to children), or increased FOP labeling requirements, whether at the federal, state, or local level – despite these being key policy measures endorsed by the WHO to address obesity and diet-related NCDs. However, ATNI did find evidence of some companies and their trade associations lobbying against such measures in the LDA database, e.g. the ABA against SSB taxes in 2021, while similar activities have been reported in California.

Trade Associations

Since legislation affects companies collectively, lobbying is often undertaken by trade associations on their behalf. However, this can obscure which companies’ interests are being represented in lobbying, as well as removing direct responsibility for these companies for the associations’ actions. Therefore, to enhance accountability, companies must be transparent about their trade association memberships and levels of involvement in them.

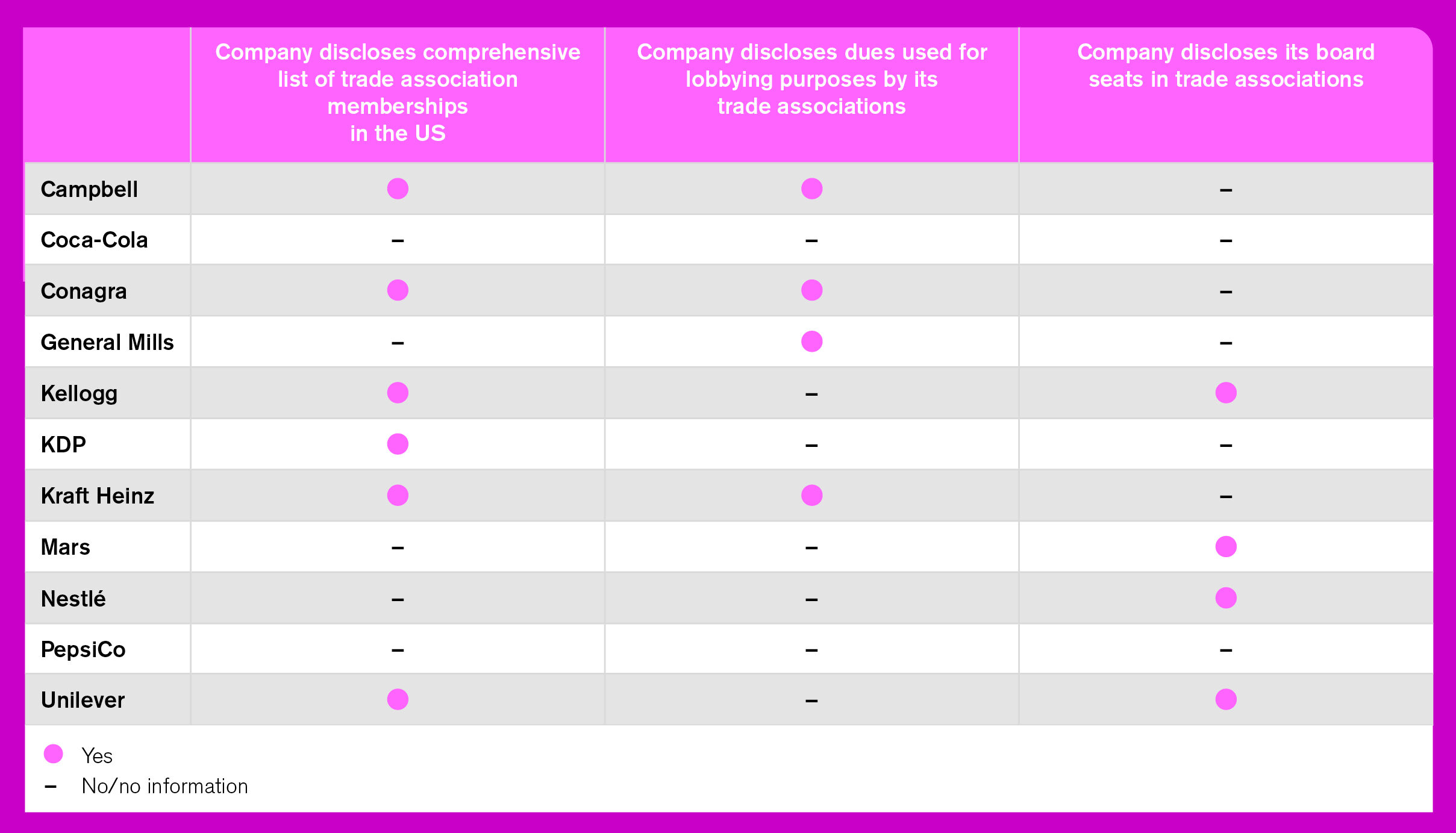

Only five companies disclose their trade association memberships in the US to a reasonable level of comprehensiveness: Conagra, Campbell, KDP, Kellogg, and Unilever. The others either only disclose memberships to which it pays dues over a relatively high threshold (e.g. > USD 20,000), or only provide an indicative list without explanation. Moreover, only four companies (Conagra, Campbell, General Mills, and Kraft Heinz) disclose the precise amount of their membership dues that are used for lobbying purposes. Meanwhile, since 2018, Kellogg, Unilever, and Nestlé have started indicating which trade associations they hold board seats on, alongside Mars, which was found to do so in 2018.

Table 1. Disclosure relating to trade association memberships in the US

Political Contributions

Another means of influencing policymakers is through political finance contributions, which are made either directly from the company’s treasury (for state and local candidates only) or indirectly via PACs. Many companies also have ‘employee PACs’ that use funds contributed by the companies’ executives, shareholders, lobbyists and their families, as well as their staff. The PACs are able to donate to candidates at a federal level and can therefore be highly influential. Nestlé, Unilever, and Mars have policies in place to prohibit any such donations in the US.

There are regulations around whether and how companies can make political contributions in the US, as well as stringent disclosure requirements on the Federal Election Committee (FEC) registry. Nevertheless, many companies go beyond mandatory disclosure and demonstrate commitment to transparency by publishing detailed information about their political contributions on their own domains. Encouragingly, all companies (except Kraft Heinz) were found to publish comprehensive information about their political contributions from their company treasury. Regarding contributions from ‘employee PACs,’ only Coca-Cola, Kraft Heinz, PepsiCo, and Conagra published detailed information about their activities; General Mills, KDP, and Kellogg only publish the name of the employee PAC, while Campbell recently dissolved theirs, but did not publish information about its recent activities.

Lobbyists and Lobbying Firms

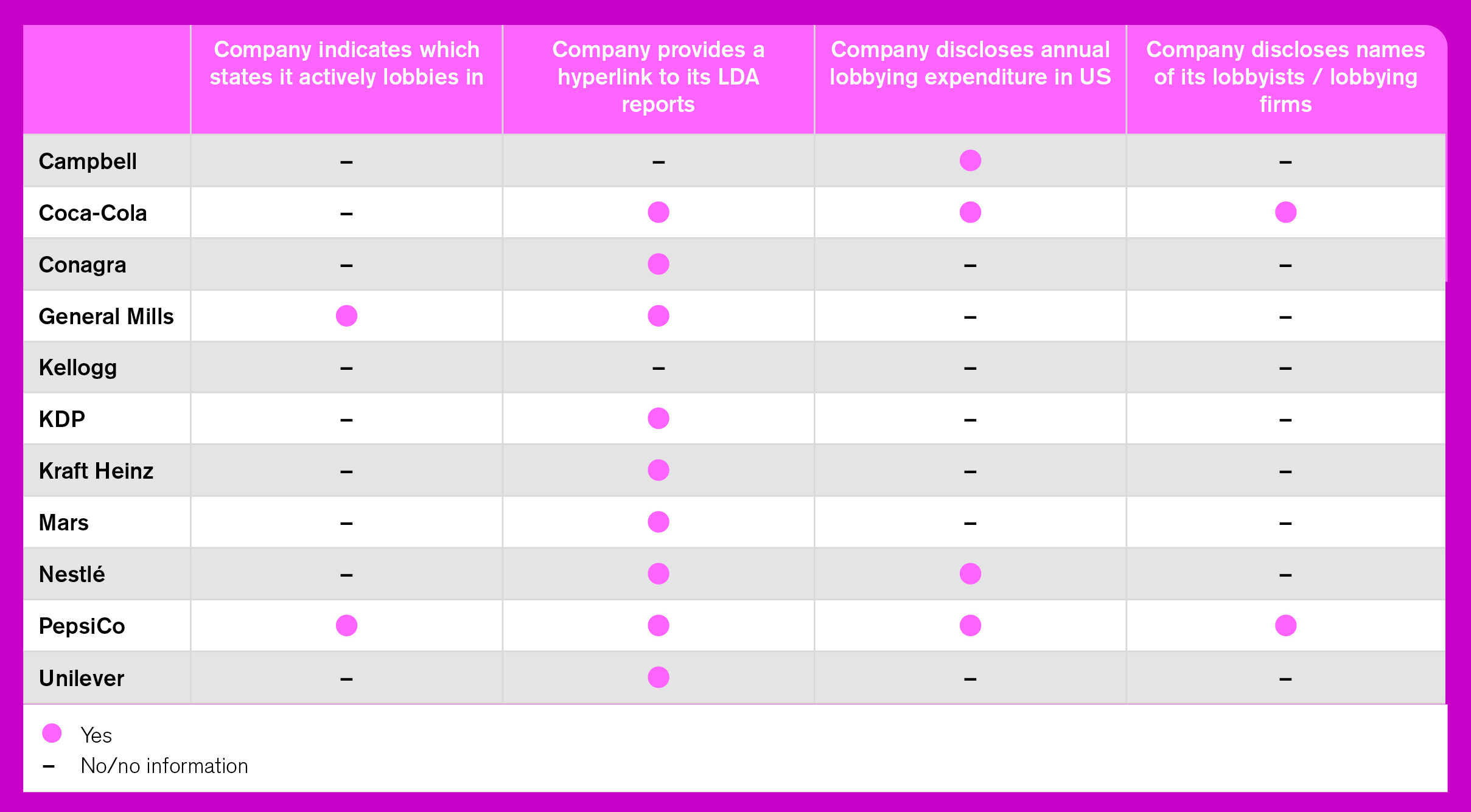

While companies are required by law in the US to disclose basic information about their lobbying activities on public registries at the federal level and in most states, they can still go beyond this and demonstrate their commitment to transparency by publishing this information on their own domains, along with additional information not captured by mandatory disclosure. At a basic level, all but two companies provide hyperlinks to one of the searchable LDA websites on their public domain. Coca-Cola goes even further, publishing its quarterly lobbying reports directly on its website.

General Mills, meanwhile, also provides hyperlinks for the lobbying registries of the two states which it lobbies in, while PepsiCo indicates the states in which its lobbyists are active; no other companies indicate in which states they actively lobby. Given that state-level policymaking is also an important arena for lobbying – with public health policies at this level affecting millions of people – it is important that companies are also transparent about their lobbying activities below the federal level. Disclosing which states they actively lobby in is a good first step: it saves interested stakeholders the significant labor involved in checking each state register manually.

Moreover, only four companies (PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Nestlé, and Campbell) publish the total amounts spent on lobbying in the US each year on their own domains. PepsiCo, meanwhile, is the only company to disclose the names of the lobbyists and lobbying firms it contracts, both at federal and state levels. While this is a mandatory requirement for lobbying registries, publishing on its own domain enhances transparency by enabling stakeholders to recognize and scrutinize the third-party actors lobbying on behalf of the company more easily.

Table 2. Disclosure relating to lobbying activity and expenditure

Lobbying Positions on Key Nutrition-Related Policies

It is crucial that companies disclose their lobbying positions for key nutrition-related policies, as this helps to ensure consistency in the company’s lobbying activities (incl. via trade associations) and is key to enhancing accountability. Important policy positions that ATNI encourages a company to disclose on include the aforementioned WHO-endorsed measures: fiscal measures to address obesity, restrictions on marketing to children, and mandatory FOP labeling requirements.

Generally, disclosure on these topics was very low among the companies assessed. While some companies, such as Nestlé and Kellogg, disclose lists of topics on which they are active in lobbying, they do not disclose their specific positions or use ambiguous language in doing so. PepsiCo and Coca-Cola indicate that they oppose SSB taxation to address obesity (but are transparent about doing so). Meanwhile, Campbell and PepsiCo indicate a clear preference for self-regulation with regard to marketing to children, rather than government regulation.

Notable Example: An exception is Unilever, which now publishes a range of ‘Advocacy and Policy Asks’ on its website, including each of the measures listed above. Moreover, in its ‘Position on Sugar’ and ‘Position on Nutrition Labeling’ documents, the company provides additional detail, publicly specifying under which conditions the company would support (or not support) certain policies.

Notable Example: Also worth highlighting is General Mills, which provides hyperlinks directly to several of its policy consultation comments and letters to policymakers on its website, a practice also demonstrated by the SFPA.

-

Most companies could strengthen their lobbying management systems by conducting internal and/or independent third-party audits of their lobbying activities and disclosure to ensure alignment with their policies and/or codes of conduct.

-

Companies are encouraged to actively support (or commit to not lobby against) public policy measures in the US to benefit public health and address obesity, including those endorsed by the WHO.

-

Companies are encouraged to ensure that their disclosure of trade association memberships in the US is as comprehensive as possible, including the specific dues paid that are used for lobbying purposes and any board seats held at these organizations.

-

To further enhance transparency and go beyond LDA requirements, companies are encouraged to publish comprehensive lobbying information on their own domains, rather than only on public registries. Notably, they could significantly improve their disclosure regarding the states in which they lobby, the names of lobbyists and lobbying firms they use, and the amounts they spend on lobbying in the US.

- Almost all companies could significantly improve their disclosure regarding lobbying positions on key public health policies that would affect the industry. These positions should be as specific and unambiguous as possible, including conditions and provisions if necessary, as per Unilever’s example. Publishing links to specific documents used in government engagements is also encouraged.

Box 1. Sustainable Food Policy Alliance (SFPA)

Toward the end of 2017, the US divisions of Nestlé, Unilever, and Mars left the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA, currently known as the Consumer Brands Association (CBA)) – a powerful industry lobbying group – amid disagreements over policy positions on nutrition-related topics such as labeling. In 2018, together with Danone North America, these companies established a new advocacy group, the Sustainable Food Policy Alliance (SFPA). Concerned about the “continued rise in obesity rates and other chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease, as well as food insecurity and access to healthy food in the US,” the group is “committed to developing and advocating for policies that help people make better-informed food choices that contribute to healthy eating while supporting a sustainable environment.”

Examples of legislative and regulatory issues it lobbies on include efforts to reduce dietary sodium and added sugar in consumers’ diets, updating definitions of terms like ‘healthy,’ and encouraging timely implementation of the new nutrition facts panel. The group has no permanent staff; activities are undertaken by employees of the companies themselves.

G2. Stakeholder Engagement

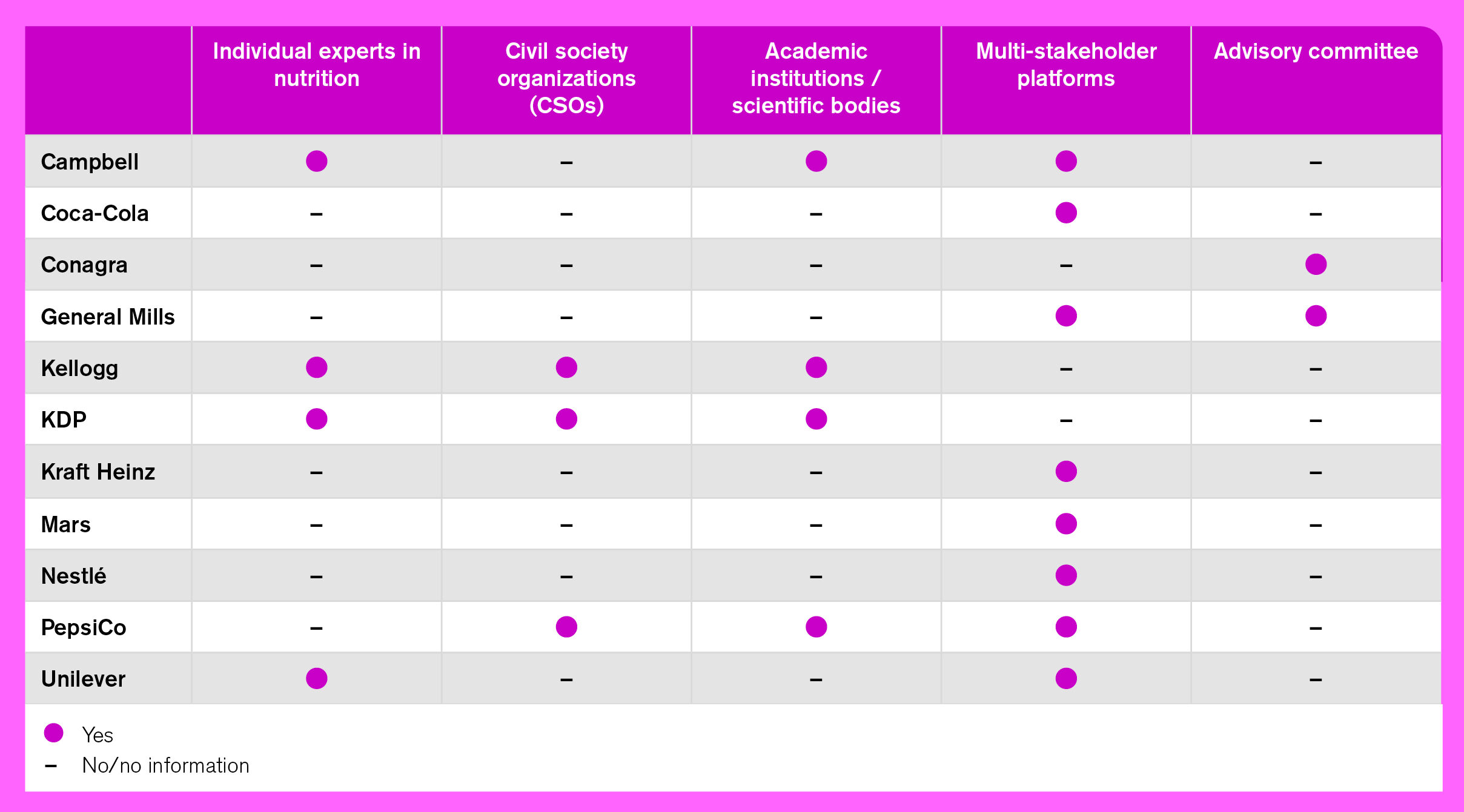

Encouragingly, all companies were able to show some evidence of engaging with nutrition-related stakeholders in the US, such as civil society organizations, academic/scientific institutions, or government bodies, on their commercial nutrition strategies and activities – whereas only six did so in 2018. Moreover, eight companies did so with a wide range of stakeholders; only Coca-Cola, Kraft Heinz, and Conagra were more limited.

Table 3. Stakeholder groups company showed evidence of engaging with on nutrition-related topics

This stakeholder engagement takes a variety of different forms. On one hand, Campbell, Kellogg, KDP, PepsiCo, and Unilever each indicated that they undertook targeted one-on-one consultations with external stakeholder groups who have relevant expertise regarding specific aspects of their nutrition-related activities.

Notable example: KDP now reports that it engages with external, credentialed experts in public health, nutrition, fitness, mindfulness, and academia, as well as the Partnership for Healthier America and other public health-oriented civil society organizations, to help shape its nutrition-related activities. This includes the development of its ‘Positive Hydration’ strategy and discussing the marketing of its beverages.

In addition, most companies (Mars, Nestlé, and General Mills in particular) indicate they engage with other stakeholders via membership in multistakeholder initiatives, such as the Portion Balance Coalition; the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)/Institute of Medicine (IOM) Food Forum; Obesity Roundtable; and Tufts University Food and Nutrition Innovation Council – all of which serve as platforms for convening stakeholders with different perspectives and for sharing information.

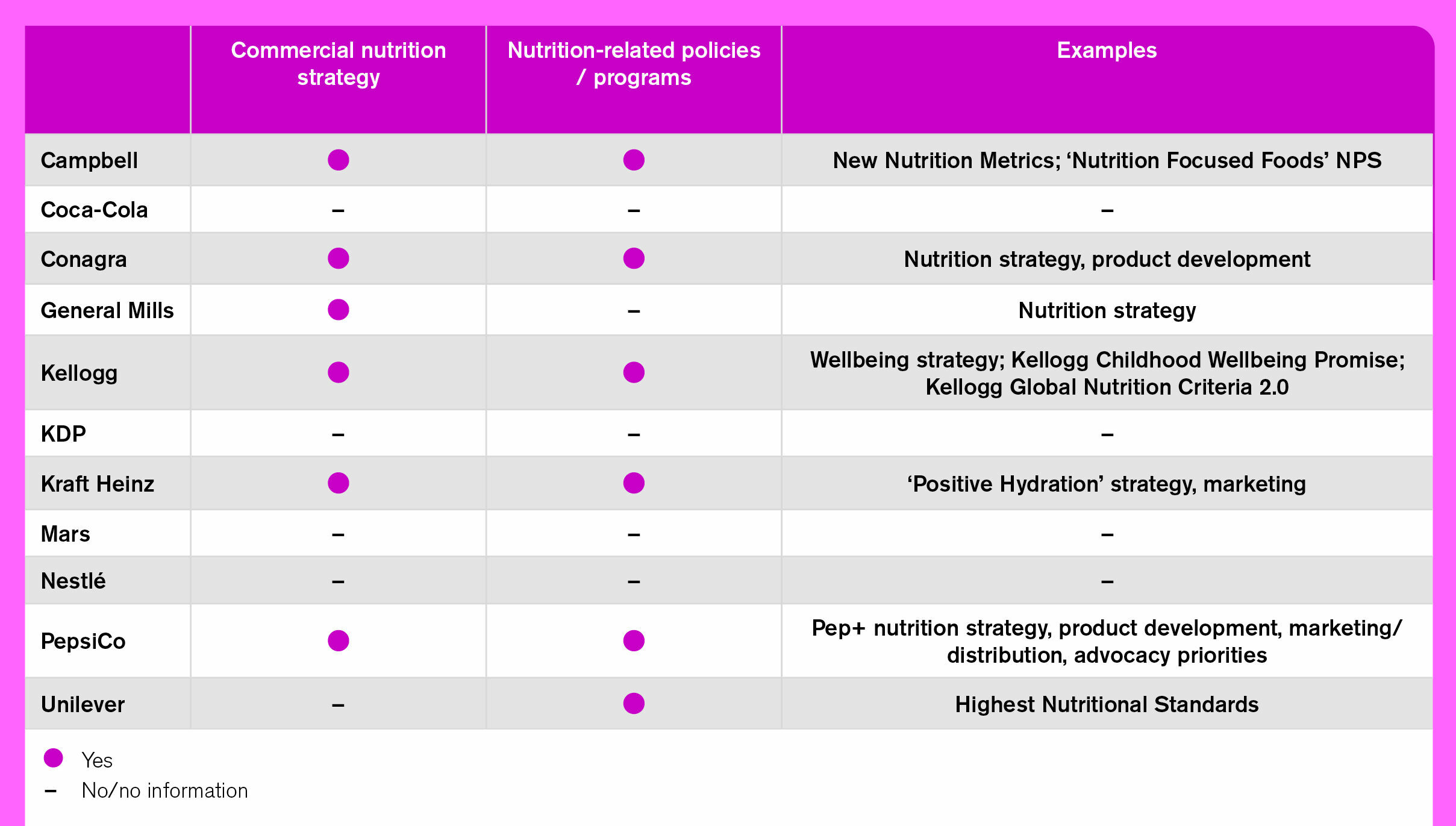

Campbell, Kellogg, KDP, and PepsiCo each showed that they engaged stakeholders on multiple different aspects of their nutrition strategies, policies, and programs. KDP, for example, developed its ‘Positive Hydration’ strategy with the help of Partnership for a Healthier America (PHA). It also showed evidence of discussing the marketing of its carbonated drinks with the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) and its health and wellbeing strategy with a group of environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG)-focused investors. Campbell, meanwhile, states that it engaged with external nutrition experts regarding its nutrition strategy, the new Nutrition Metrics and ‘Nutrition Focused Foods’ profiling system. Similarly, Kellogg states that it consulted AHA, expert dieticians, and scientists in the development of both updated Kellogg Global Nutrient Criteria and its Childhood Wellbeing Promise.

The remaining companies, however, either only provided one specific example (General Mills and Unilever) or were less specific about the nature and content of these engagements. This is especially the case for those relying predominantly on engagement via multistakeholder platforms and initiatives, relative to those with clear one-to-one engagement.

Table 4. Subjects of companies’ nutrition-related stakeholder engagement

While the level and quality of engagement have certainly improved since 2018, disclosure regarding these engagements has lagged significantly. No companies were found to publicly disclose the full range of stakeholders they engaged by name, either at an organizational or individual level. This is essential for transparency and accountability purposes. While companies tend to publicly state that they conduct systematic stakeholder engagement, very often they only publicly reference broad categories of stakeholders without specifying their identities. This prevents scrutiny regarding the relevance and legitimacy of these stakeholders and, therefore, of the engagement itself.

Another key aspect of disclosure missing is the financial element: whether or not (and to what extent) the engagement involved some form of compensation for the external expert’s time, or whether an organization or initiative engaged receives sponsorship or other funding from the company. This is concerning, since the bias-inducing impact of compensation and sponsorship is well-documented. It is not unreasonable to expect an expert’s time to be compensated or an organization to be supported in exchange for access to its expertise. Nevertheless, it is important to disclose information about such transactions to enable stakeholders to decide for themselves the extent to which these are proportionate and legitimate.

A third aspect of disclosure found to be lacking are the details of the content of the company’s engagements. Only three companies (Kellogg, Campbell, and KDP) publicly report which specific aspects of their activities were the subject of their stakeholder engagements. Moreover, almost no companies publicly report the outcomes of their engagements or how their practices were adapted as a result; those that do only do so in broad terms, lacking specifics.

While large companies have the advantages of considerable resources and wide consumer reach, there are nevertheless sensitivities involved with private, for-profit companies engaging in nutrition education campaigns. It is essential that those who choose to do so only support those designed and implemented by independent stakeholders with relevant expertise – or involve them heavily in the process – and ensure that they are aligned with public sector guidance (such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans).

Campbell, General Mills, Unilever, and Conagra each showed that they only support such programs. General Mills’ projects in Minneapolis and Buffalo, which involve “health services and food and wellness education” and “culinary and food skills training for youth,” are designed by two local United Way organizations, while also providing grants to independent non-profits active in these areas. Meanwhile, Campbell’s new ‘Full Futures’ program sees different partner organizations run different parts of the program: ‘The Food Bank of South Jersey’ provides nutrition education to students and parents, two youth advisory councils advise on the ‘Full Futures’ work, and the ‘Alliance for a Healthier Generation’ leads the measurement and evaluation work.

The remaining companies all run a mix of programs designed by themselves and external groups, while Kraft Heinz states that it does not engage in any such activities in the US.

-

Companies should ensure that – in the process of developing a new nutrition strategy, policy, or other nutrition-related activity, or when updating or reviewing an existing one – they engage directly with a range of stakeholders, such as civil society organizations, academic institutions, and scientific bodies with recognized expertise in nutrition and public health.

-

All companies could significantly improve their transparency regarding which specific stakeholders they engage with and the identities (or, at minimum, affiliations) of experts they have consulted, as far as possible. In addition, the degree of financial compensation for these engagements should be disclosed.

-

All companies are encouraged to improve the public reporting of the topics of discussions during stakeholder engagements, along with which aspects of the company’s nutrition-related activities are being discussed. Importantly, companies should also be clear about the outcomes of the engagement, and if and how they were used to change their practices or plans.

- Companies that choose to support consumer nutrition education are encouraged to ensure that such programs are designed and/or implemented by independent groups with recognized expertise, and that they are aligned with public sector guidance (such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans).